About the Hearth Tax Digital website

Hearth Tax Digital replaces Hearth Tax Online (2010-2017). Launched in 2019, the new site is a platform for the publication and dissemination of research and analysis on hearth tax records and other associated documents. It acts not only as a portal through which the Centre for Hearth Tax Research can circulate data and findings, but also as a forum for other research centres, historical groups or individuals to publish work allied to hearth tax studies.

The on-going work of the Centre for Hearth Tax Research means that new transcripts and analyses are being continually produced and, consequently, Hearth Tax Digital will be frequently updated as new counties are completed. This blog will feature the latest news on updates, events and progress on new material.

The primary objective of the Centre for Hearth Tax Research is to publish, in a hard-copy volume, the best surviving hearth tax return or returns for every county in England where a satisfactory return has not already been published. However, this represents a long-term project and it will be several years before some county volumes are completed. Hearth Tax Digital, therefore, provides the opportunity to publish limited access to the personal name data for previously published and forthcoming counties as well as analysis about the distribution of both population and wealth and poverty in county communities. Hearth Tax Digital provides free access to personal name data as well as analysis about the distribution of both population and wealth in urban and rural communities in England. The website provides full text search, search by numbers of hearths taxed, and a ‘data basket’ in which the user can store single entries for further analysis.

Hearth Tax Online website removed following cyber attacks

29th September 2017

The popular online resource, created by the University of Roehampton, will have to be completely rebuilt.

The Hearth Tax Online website, run by the Centre for Hearth Tax Studies at the University of Roehampton, has had to be taken down due to an aggressive spate of cyber attacks that left users being taken to alternative sites.

Dr Andrew Wareham, director of the Centre, told Who Do You Think You Are? Magazine that the resource was attacked "by over 400 malicious scripts" and that "the extent of the attack was so great that it means that we are going to need to rebuild the website".

Although the resource is likely to be down for some time, Wareham added a note of optimism: "The good news is that I am putting into place something that will result in a better website, in terms of its security, content and usability."

In the meantime, here are details of five other websites that we recommend for 17th century research.

New Hearth Tax Website

13th March 2019

Hearth Tax Digital - an exciting new website has been launched by the University of Roehampton's Centre for Hearth Tax Research in partnership with the University of Graz' Centre for Information Modeling. The Roehampton-Graz website has been designed by Professor Georg Vogeler and Dr Andrew Wareham, and it has been built by Theresa Dellinger and Jakob Sonnberger, with financial support from the British Academy and the Department of Humanities at the University of Roehampton.

As a result early modern historians, local historians, family historians and genealogists now have full access to an increasing number of records of the Restoration hearth tax in a single searchable database. The database enables searches across returns and counties. At present the site has the records for London & Middlesex and Yorkshire East & West Riding, and over the next six months data for more cities and counties will be added.

The team has been working on the intersection between Digital Humanities, local and regional history and the documentary study of the Restoration hearth tax. The new website represents a breakthrough in hearth tax studies and makes a major contribution to the digital humanities, transforming our understanding of this source to provide deeper insights into early modern society.

Digital approaches to taxation records, such as the hearth tax, have typically used databases and spreadsheets (eg Access and Excel) to extract data on numbers of taxpayers/households, indexes of taxable wealth/hearths and payment status. The data can be quickly sorted and interrogated and compared with other numerical datasets, and these approaches have been particularly popular in the social sciences, especially with economists interested in working with historical data.

But this approach is of less value to historians and students interested in social and cultural history. The problem is twofold:

- firstly, the cleaning of the data required for a database structure results in the removal of all the extraneous data on the personal circumstances of taxpayers, and

- secondly, readers are not able to follow collectors as they went from house to house to collect the hearth tax.

In the medieval and early modern periods, plague, fire, famine and other disasters were part of the everyday experience and information on these problems find their way regularly into the hearth tax records. But because these marginal notes were not recorded in a systematic way in a tabular format they cannot be captured readily through databases. For instance, there may be a sequence of entries providing references to tax-payers who were blind in a particular locality and/or as the result of the work of a particular collector.

Social and cultural historians are likely to capture such information through textual descriptions supported by Word tables (just as powerful as Excel if you are doing basic calculations), and this is a very powerful tool if one is interested in a series of micro or local history case studies. But it is of limited use once the data starts to build up to cover a multitude of locations. However this new database technology on Hearth Tax Digital would allow the user to combine numerical and textual data to search for all references to blind people living in properties with one or two hearths, as opposed to three and four hearths.

Hearth Tax Digital has four key features. There is

- a general search button which allows users at any time to do any textual search - by personal name, location or descriptor. (All searches enable you to move from the results of the search to the record in which the results were found.)

- a records page which allows readers to read the entries in the returns, together with the preliminary information, as they were written in the original returns and assessments.

- the databasket which allows users to click on all the entries which they are interested in for further use.

- an advanced search function which allows users to combine searches for people and places with numbers of hearths.

As the team worked on the project it became clear that this technological advance, which took account of nuanced understanding of the hearth tax records, opens the door to other early modern records allowing them to be read and searched in the same way. As a result on the about page, a statement has been added to encourage those who may have similar digital records to approach us to see about making these available on Hearth Tax Digital.

Hearth Tax Digital

alpha version

About this web site

The web site is run and maintained by the Austrian Centre for Digital Humanities (University of Graz, Austria) and Centre for Hearth Tax Research (University of Roehampton, UK) and supported by the British Academy. The research published on this web site has been undertaken with the generous assistance of the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the British Academy, the Marc Fitch Fund and the Aurelius Trust.

Hearth Tax Digital is a platform for the publication and dissemination of research and analysis on hearth tax records and other associated documents. It provides a unique window on society and the social character of England in the late seventeenth century.

It acts both as a portal through which the Hearth Tax Project & Centre can circulate data and findings, and also as a forum for other research centres, historical groups or individuals to publish work allied to hearth tax studies.

The on-going work of the Hearth Tax Project & Centre means that new transcripts and analyses are being continually produced and, consequently, Hearth Tax will be updated as new counties are completed.

The objective of the British Academy Hearth Tax Project & Centre for Hearth Tax Research is to explore the hearth tax records and make them more widely known. This is achieved through its hard-copy series, published in partnership with the British Record Society and through a variety of outreach activities.

Hearth Tax Digital provides free access to personal name data as well as analysis about the distribution of both population and wealth in urban and rural communities in England. If you have any data, analyses, articles, maps or any other material that you think would be suitable for publication through Hearth Tax Digital, we would be very happy to hear from you.

The digital version

This resource tries to demonstrate, how the hearth tax records can be represented in the digital medium. Therefore, it neither is a simple copy of the originals, nor a reproduction of the printed version, nor a collection of analytic data files. Instead, it takes the 'assertive edition' approach (Vogeler 2019), i.e. it tries to combine transcription with data representation. The main organisation of the edition follows the archival records preserving the documentation from the hearth tax administration (Records). These transcripts should provide the information beyond the single entries of taxation, which includes names of officials involved and comments on the process of taxation. The transcripts are encoded following the guidelines of the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI P5). They include references to a formal representation of the data contained in the texts in the ana attributes. This formal data is represented in graphs following the recommendation of the W3C for the Resource Description Framework (RDF). The schema describing the RDF graph is a basic taxation ontology (WebVOWL visualisation): The assessments and returns record taxation acts (htx:Taxation, in which somebody is taxed (htx:of htx:Taxpayer) on a specific property (htx:on). The ontology and the RDF files form the database of Hearth Tax Digital, which is the basis for the search and the calculations in this site.

The website provides fulltext search, search by numbers of hearths taxed, and a 'data basket' in which the user can store single entries for further analysis. Please be aware that the data basket is stored locally on your own computer, so it might be different when changing machine, and all data can be lost if your browser uses restrictive caching mechanisms.

Hearth Tax digital was created in a collaboration by the Centre for Hearth Tax Research at Roehampton University with the Zentrum für Informationsmodellierung, Universität Graz, funded by the British Academy in 2018/2019. It is hosted in the humanities digital archive infrastructure of Graz University, the GAMS.

The transcription project

Tracing our ancestors as far back as the mid 17th Century will soon be made much easier through an exciting new project to put ancient tax documents onto both microfilm and the internet.

The hearth tax was levied between 1662 and 1689 on each householder according to the number of hearths (fireplaces) in his/her occupation. The administrators were required to compile lists of householders with the number of their hearths according to county. The returns from the 1662 to 1689 "Hearth Tax" are one of the great taxes that form the biggest records on population in England and Wales between the Domesday Book and the 1801 census. This particular one has never been analysed precisely because it is so big. But with the help of £85,100 from the Heritage Lottery Fund, the history department at the University of Surrey Roehampton is doing just that.

The documents, in the Public Record Office and many of them fragile, will be copied onto a master microfilm and then copied to all relevant local record offices across the country. This information will then be indexed and placed on the internet.

What was the Hearth Tax ?

The Hearth Tax was introduced in England and Wales by the government of Charles II in 1662 at a time of serious fiscal emergency. The original Act of Parliament was revised in 1663 and 1664, and collection continued until the tax was finally repealed by William and Mary in 1689. Under the terms of the grant, each liable householder was to pay one shilling for each hearth within their property for each collection of the tax. Payments were due twice annually, at Michaelmas (29 September) and Lady Day (25 March), starting at Michaelmas 1662.However, the administration of the tax was extremely complex, and assessment and collection methods changed radically over time. As a result, the majority of the surviving documents relate to the periods when the tax was administered directly by royal officials, who returned their records to the Exchequer, namely the periods 1662 to 1666 and 1669 to 1674. Outside these periods, the collection of the tax was 'farmed out' to private tax collectors, who paid a fixed sum to the government in return for the privilege of collecting the tax. These private tax collectors were not required to send their assessments into the Exchequer, although a few returns from these periods do survive.

What information do Hearth Tax returns give ?

No tax return can be used as a total census of the population - there were always exemptions and evasions. The most complete Hearth Tax records are those for 25 March 1664. Information supplied includes names of householders, sometimes their status, and the number of hearths for which they are chargeable. The number of hearths is a clue to wealth and status. Over seven hearths usually indicates gentry and above; between four and seven hearths, wealthy craftsmen and tradesmen, merchants and yeomen. Between two and three hearths suggests craftsmen, tradesmen, and yeomen; the labouring poor, husbandmen and poor craftsmen usually only had one hearth. There are many gaps in the records, partly because of the loss of documentation, but partly also because of widespread evasion of this most unpopular tax. Hearth Tax returns for particular areas have been published by many local record societies, and some records are to be found in county record offices, among the quarter session records.

The tax was collected using the administrative divisions of the time - counties, hundreds, boroughs, parishes, etc. - and researchers should be aware that these have often changed over time. Basic details can be found in the E 179 database, and more specific information is available in reference works such as volumes of the Victoria County History and publications of the English Place-Name Society.

Did everyone pay the Hearth Tax ?

By the terms of the 1662 Act, only people whose house was worth more than 20 shillings a year and who were local ratepayers of church and poor rates, were required to pay the Hearth Tax. This actually left out quite large numbers of people such as paupers who paid neither church nor poor rate and people inhabiting houses worth less than 20s a year who did not have any other property over that value, nor an income of over £100 a year. Also exempt from the tax were charitable institutions with an annual income of less than £100 and industrial hearths such as kilns and furnaces (but not smithies and bakeries). However, the tax-collectors were required to collect exemption certificates from those not eligible to pay, and you may need to check these as well.

Exemption certificates

Most individuals who were not liable to pay the hearth tax for reasons of poverty were required to obtain a certificate of exemption from the parish clergyman, churchwardens and overseers of the poor, countersigned by two Justices of the Peace. After the revising Act of 1663, hearth tax officials were to include in their assessments lists of those chargeable and not chargeable (exempt). However, the methods of recording those not chargeable tended to vary, with some assessments containing the names of exempt individuals, and others simply a record of the total number. From 1670, printed exemption forms were introduced, replacing earlier manuscript certificates; these were filled in as necessary by the local officials to record the names and assessments of the exempt in a given area. This important source may be used to supplement those assessment rolls which only show numerical totals of individuals not chargeable.

Most of the surviving certificates of exemption may be found in series E 179, mainly in large collections arranged by county. However, since many are not yet listed in detail and may be fragile, readers should ensure that they preserve the current arrangement and take particular care when handling these documents.

How to find Hearth Tax records

The majority of the surviving hearth tax documents can be found amongst the records of medieval and early-modern taxation in series E 179 at The National Archives. The main means of access to these records is now the E 179 database also at the National Archives. This database will eventually contain details of all documents in series E 179 relating to lay and clerical taxation in England and Wales between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries, providing accurate and up-to-date information on their nature and contents, and indexes of all place-names contained within them. The database is searchable by place, date, tax and document type, or any combination of these. Readers should be aware that names of individual taxpayers are not included in this database, but that they may use the database to search for documents containing such names, prior to examining the original document or, where available, a printed transcript. The database is also linked to both the on-line Catalogue and, for readers at Kew, to the document ordering service.

In addition to assessment documents, a large quantity of material relating to the accounting procedures of the hearth tax also survives, both in series E 179 and elsewhere, including the account rolls in series E 360. For financial details and specific references, see the work of C.A.F. Meekings in:

- Analysis of Hearth Tax Accounts 1662 to 1665, List & Index Society, vol. 153 (1979)

- Analysis of Hearth Tax Accounts 1666 to 1669, List & Index Society, vol. 163 (1980)

Introduction

The hearth tax was introduced in England and Wales in 1662 to provide a regular source of income for the newly restored monarch, King Charles II. Parliament had accepted in 1662 that the King required an annual income of £1.2 million to run the country, much of which came from customs and excise. By 1661 the sum was short by £300,000, a figure that the hearth tax was projected to yield but which proved to be a hopeless overestimate. The government sought to raise this money by a means which had no Commonwealth links such as the excise or the assessments and the MPs ensured that it did not impinge too heavily on those with land and personality such as themselves. Unlike other contemporary levies the tax was granted in perpetuity.

Principles of the tax

Sometimes referred to as chimney money, the hearth tax was essentially a property tax on dwellings graded according to the number of their fireplaces. The 1662 Act introducing the tax stated that "every dwelling and other House and Edifice … shall be chargeable … for every firehearth and stove … the sum of twoe shillings by the yeare". The money was to be paid in two equal instalments at Michaelmas [M] (29 September) and Lady Day [L] (25 March) by the occupier or, if the house was empty, by the owner according to a list compiled on a county basis and certified by the justices at their quarterly meetings. These quarterly meetings conducted within each county were known as the Quarter Sessions. The lists of householders were an essential part of the administration so that the returns of the tax could be vetted and for two periods 1662-6 and 1669-74, one copy of the relevant list was returned to the Exchequer and another was held locally by the clerk of the peace who administered the Quarter Sessions.

The administration of the tax

Frequent changes in administration were a feature of the tax in an effort to reach its unattainable projected yield. Initially in 1662 assessment and collection were entrusted to the local government officials - petty constables or tything men supervised by the high constables and the sheriffs. The return of money to the Exchequer was so slow however that a revising Act was passed in 1663 which tightened up the assessment procedure. A further Act in 1664 supplemented the local officials with professional tax collectors directed by a county receiver appointed by the King.

By the spring of 1666, the King was so short of money that the receivers were peremptorily removed and the tax was privatised with a consortium of London merchants paying up front for the privilege. Some receivers had already begun the 1666L collection but in most counties it was managed by the farmers although audited by the Exchequer. The farm was a failure exacerbated by the Great Fire of London which destroyed the tax office and as a result the contract was terminated at the earliest possible opportunity at 1669L. It was not until the summer of 1670 that a second receivers' administration was set up with county lists again being returned to the Exchequer. Because of this late start, the officials had to make two collections that of 1669M and 1670L retrospectively. At 1674M the organisation reverted to farmers again. Farming was continued until 1684 with two five-year contracts being drawn up. Finally in 1684 the administration was combined with that of the Excise under a Commission. The persistent problems of assessment and collection were reflected in ten abortive bills concerning the tax being introduced in the Commons between 1669 and 1681. The situation was not helped by the fact that from1663 the officials had the right to search each dwelling to check the number of hearths. Finally the tax was repealed in 1689 at the start of William and Mary's reign in order to gain popularity.

The tax was collected according to the administrative units of the time namely county, hundred and constabulary or township, which may or may not be the same as the parish. In the cities, towns and boroughs the constables or sub-collectors often worked according to wards whose boundaries again may or may not be the same as those of the parish. As time went on there was a streamlining of the administrative areas, the county towns and boroughs being absorbed within their respective counties and some other counties being amalgamated.

Yields of the tax

At no time in its life did the tax yield its expected target of £300,000 per annum. The first two collections raised only £115,000 and by 1666 the annual net yield had fallen to about £103,000. The subsequent changes in management saw a gradual increase in annual net yield from about £145,000 in 1670 to £157,000 in 1680 and under the Commission from 1684 to 1689 it reached its highest net total of £216,000 per annum.

Exemption from the tax

By the 1662 Act certain hearths were made not liable namely those in houses already exempt from paying local taxes to church and poor due to "poverty or smallness of estate", and those in dwellings whose rentable value at market rates was 20 shillings a year or less and whose occupiers did not have or use any land or tenements of their own or others exceeding that value nor had any goods worth more than ten pounds. For those in this second category a certificate was required signed by the minister, and at least one of the churchwardens or overseers of the poor of their parish and certified by two justices. Such certificates of exemption were valid for one year or two collections.The 1664 Act limited exemption still further by restricting it to dwellings with no more than two hearths and furthermore no hearth which had previously been chargeable could be made exempt unless it became ruinous. A third category of hearths in blowing houses, stamps, furnaces and kilns and those in hospitals or almshouses below a certain annual income was also exempted. Throughout the life of the tax the identification of the not liable was primarily the responsibility of the parish officials who not infrequently were challenged by the professional tax collectors thereby causing friction between the two sets of administrators.

Survival of useful lists

The hearth tax has left many records but the most well-known and heavily-used are the county lists of householders which only survive when the Exchequer controlled the administration between 1662M to 1666L and 1669M to 1674L. Usually about four returns were compiled for each county in each period and generally at least two have survived in a legible form for most areas although many are incomplete. In addition, some lists are abbreviated versions merely recording those householders whose hearth number had changed since the previous collection. Most of these records are held at The National Archives and details can be accessed through its E179 database. Some may also be found in local record offices, amongst estate papers and in the British Library, generally but not always belonging to the same periods as those in The National Archives. A selection of transcripts of county lists have also been published.

Recording of the not chargeable

The legal clauses stating the requirements for exemption were drafted rather loosely which together with poor instructions led to much misunderstanding amongst the officials. As a result the recording of the not liable in the county lists is inconsistent and may even be omitted. In 1662 only the names of the chargeable were to be noted but from 1664L the not chargeable were also required to be listed separately. From then on they were included in a bewildering diversity of ways. The records of 1664M-1665 may note the exempt separately or some may be included amongst the chargeable. Most of the returns dated 1669M to 1674L record chargeable and sometimes the not chargeable grouped under various headings such as 'certified', 'not chargeable' or 'receive alms'.

If the names of the exempt have been omitted or truncated it may be possible to extract them from the exemption certificates which are also held at The National Archives. Whilst the earlier certificates were generally compiled on an individual basis, the later introduction of printed forms permitted all or many of the exempt of one parish to be listed on one certificate. Most of these certificates derived from the 1670s are as yet uncatalogued and not all counties are represented.

Description of lists

Normally each entry cites a number of hearths and the name of an individual who may be the occupier or the owner. Where the entry includes more than one hearth the number sometimes represents hearths in several buildings or a sub-divided one. Within a rural area the simple list of householders gives no indication of the relationship of each entry to another on the ground but in the towns, if inn names are recorded it may be possible to trace partially the steps of the tax official.

In some lists the names and numbers represent those who were assessed for the tax and in others those who had or had not paid because the returns were compiled at different stages of the appropriate collections. Sometimes for certain collections due to changing instructions, additional information is given such as a change of occupier or a change in hearth number.

Warnings and limitations

Only in the scattered instances where building names are recorded can the hearth number be related to a specific building although a titled entry or that of a cleric may provide a clue. The absence of a specific name in a place does not necessarily mean that such an individual was not living there. Since the county lists only record the name of the occupying householder or owner, the missing individual could have been living with other members of his family, listed as a householder under another township or perhaps he/she was categorised as exempt for which notification on the lists is notoriously unreliable.

Each list for whatever collection is an amalgam of several people's work so that the amount of information recorded within it may not be consistent due to the varying ability and assiduity of the officials. All the returns are copies of original working lists or previous records so they are subject to copying and spelling errors, a problem made worse where the compiler was unfamiliar with local names. For each county there is no one 'best buy' in terms of completeness of recording but comparisons with lists of a different date where they survive is essential to help identify omissions and errors.

The Hearth Tax was the subject of the BBC2 history series Breaking the Seal explained by a Roehampton PhD student. The tax itself was abolished by King William III in 1689 due to its mass unpopularity, mirrored by hostility to the Poll Tax over three hundred years later. One of its problems was administration, made worse by the Great Fire of London, which destroyed the newly established Hearth Office.

Genealogists can use the information to trace back family trees because the best Hearth Tax returns accounted for and named every householder in each county, whether they were liable or exempt from paying the tax. Of course tax evasion was as much of a problem in the 17th century as it is today! As the tax was based on the number of hearths per household it can be used not only to estimate population size but also distribution of wealth, social status and problems of poverty.

Professor Margaret Spufford, research professor in history at the University of Surrey Roehampton, saw the need to have this information made widely accessible and gained support from leading archivists and historians for the project.

The project is underway and news of progress and recent and forthcoming events is published on the University's website.

The British Record Society has joined with the Roehampton Hearth Tax Centre to produce a series of texts of the Hearth Taxes of the 1660s and 1670s. These are being published, county by county, generally in conjunction with the relevant local record society. There may well be some twenty volumes in the series. They will make available lists of inhabitants, and the size of houses they occupied, village by village across England.

The volumes are provided with scholarly introductions complete with maps and tables so that the volumes can be of the greatest use to social and economic historians working on a national canvas as well as to the local historians of the counties concerned.

When the mapping and analysis is completed, it will provide a bird's-eye view of the distribution and density of taxable population in England and Wales in the 1660s and 1670s.

The introductions also stress that the Hearth Taxes throw light on the buildings about which they give such austere information. It is not useful to count hearths without some awareness of the houses that contained them. This series will therefore focus attention on housing as necessary evidence in interpreting the past.

They are also especially useful for locating lost ancestors, since they can pin down which parish registers are worth searching, whilst the house size gives some sort of indication of the status of the taxpayers themselves. In addition they are naturally ideal tools for local historians, and provide the opportunity of setting the community being studied in context.

The Roehampton Hearth Tax Centre has, with the assistance of a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund, had master microfilm made of the Hearth Tax listings in the Public Record Office, which, in turn, has made copies of the relevant portions available to every appropriate local record office in the country. The work of transcription of Hearth Tax records from microfilm is already progressing in a considerable number of counties.

Volumes published:

- Cambridgeshire Michaelmas 1664: Evans, N., & S. Rose, eds., (2000), Cambridgeshire Hearth Tax Returns Michaelmas 1664, BRS Hearth Tax Series I

- Kent Lady Day 1664: Harrington, D., S. Pearson & S. Rose, eds., (2000), Kent Hearth Tax Assessment Lady Day 1664, BRS Hearth Tax Series II

- Norwich, Thetford, Yarmouth and Lynn Exemption Certificates 1670 to 1674: Seaman, P., J. Pound & R. Smith, eds., (2001), Norfolk Hearth Tax Exemption Certificates 1670 to 1674: Norwich, Great Yarmouth, King’s Lynn and Thetford, BRS Hearth Tax Series III

- County Durham Lady Day 1666: Green, A., E. Parkinson & M. Spufford, eds., (2006), County Durham Hearth Tax Assessment Lady Day 1666, BRS Hearth Tax Series IV

- Yorkshire West Riding Hearth Tax Assessment Lady Day 1672: Hey, D., C. Giles, M. Spufford & A. Wareham, eds., (2007) Yorkshire West Riding Hearth Tax Assessment Lady Day 1672, BRS Hearth Tax Series V

- Westmorland Hearth Tax Michaelmas 1670 and surveys 1674 to 1675: Phillips, C., Ferguson, C. & Wareham, A., eds., (2008) Westmorland Hearth Tax Michaelmas 1670 and surveys 1674 to 1675, BRS Hearth Tax Series VI

- Warwickshire Hearth Tax Returns; Michaelmas 1670, with Coventry Lady Day 1666: Arkell, T with Alcock, N., eds. (2010), BRS Hearth Tax Series VII (Dugdale Society vol. 43)

- Essex Michaelmas 1670: Ferguson, C., French, H., Thornton, C.. & Wareham, A., eds (2011) Essex Hearth Tax Michaelmas 1670, BRS Hearth Tax Series VIII

- London and Middlesex Hearth Tax, Lady Day 1666: Davies, M., Ferguson, C., Harding, V., Parkinson, E., & Wareham, A., eds., (2014), BRS Hearth Tax Series IX

- Yorkshire East Riding Hearth Tax: Neave, D., Neave, S., Ferguson, C., & Parkinson, E., eds., (2016), BRS Hearth Tax Series X

These volumes are fully indexed both by surnames and by places and will be followed by:

- Bristol Hearth Tax

- Northumberland Lady Day 1666

- Huntingdonshire Michaelmas 1664

- Northamptonshire Lady Day 1674

- Lancashire Lady Day 1664

to which five volumes should be added Warwickshire Hearth Tax Returns; Michaelmas 1670, with Coventry Lady Day 1666 which I have yet to review.

| Volume | Date | Ramsdale, Ramsdall & Ramsdal Entries |

|---|---|---|

| Cambridgeshire | Michaelmas 1664 | None |

| Kent | Lady Day 1664 | None |

| Norfolk | 1670-1674 | None |

| Durham | Lady Day 1666 | None |

| Yorkshire, West Riding | Lady Day 1672 | 2 entries |

| Westmorland | Michaelmas 1670 and surveys 1674 to 5 | None |

| Westmorland | Hearth Tax Survey 1674 to 5 Fleming Manuscript |

None |

| Westmorland | Hearth Tax Survey 1674 to 5 Survey for Kendal and Kirkland |

None |

| Westmorland | Hearth Tax Survey 1674 to 5 Exemptions in Kendal 1675 |

None |

| Kent | Lady Day 1664 | None |

| Surrey | Lady Day 1664 | None |

| Worcestershire | Michaelmas Day 1664 & Lady Day 1665 | None (but see below) |

| Yorkshire, East Riding | Lady Day 1672 | 1 entry |

| Kingston Upon Hull | Lady Day 1673 | None |

| Yorkshire, North Riding | Michaelmas Day 1673 | 1 entry |

| London and Middlesex | Lady Day 1666 | None |

| Essex | Michaelmas 1670 | None |

Ramsdale, Ramsdall & Ramsdal Entries entries

Yorkshire, West Riding, Lady Day 1672

- Widd Ramsdall, 1, Staincliffe and Ewcross

- John Ramsdell, 2, Agbrigg and Morley

Worcestershire

- […] […]le, Bromsgrove, Halfshire (Ramsdale ?)

- […] […]ne, Bromsgrove, Halfshire (Blunne ?)

Yorkshire, East Riding

- Mathew Ramsdale, m. 81, Holdernesse North Bailiwick, Upton

Yorkshire, North Riding

- Rt Ramsdell, m. 1v, Halikeld, Marton le Moor

As at 12th April 2020, Hearth Tax Digital currently contains 174,347 entries of which there are only two relevant Ramsdale and Ramsdall surname entries:

| East Riding | ||||||

| ID | Text | Hearths | Status | Place | Book | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EastRiding#e_9466 | Mathew Ramsdale 1 [->] | 1 | chargeable | Upton | The National Archives (TNA) E 179/205/504 | 1672-03-25 |

| West Riding | ||||||

| WR5#h_e8138 | Widd Ramsdall 1 [->] | 1 | chargeable | Gisburn Forest | The National Archives TNA E179/210/418 | 1672-03-25 |

What can we learn from tax records?

Tax returns might bring little but misery, but they hold a lot of interest for the historian

OpenLearn 21st February 2000 (transcript)

Governments throughout history have constantly tried to tax individuals on their possessions and they've always been on the lookout for fresh indicators of wealth. In Charles II's reign, they struck at the very heart of the home. In 1662, parliament introduced a new tax. A hearth tax, sometimes called the chimney tax. Almost every hearth in the country, including this one in Penshurst Place in Kent, was taxed at the rate of one shilling. The scheme was simplicity itself. What could possibly go wrong? Elizabeth Parkinson is an expert on the hearth tax. I met up with her at the Public Record Office.

Elizabeth Parkinson, University of Surrey at Roehampton: You can see here the numbers of chimneys that are there so you can see why they were trying to tax hearths.

Bettany: This is presumably pre-the Fire of London.

Elizabeth: That's right.

Bettany: And the Public Record Office has good records of those documents.

Elizabeth: Wonderful records, unlike the window tax, of which there's very little. There's a lot.This is just a record for one county of Cornwall and they record the tax payer there and the number of hearths on which they had to pay, and of course they had to pay a shilling twice yearly, at Michelmas and at Lady Day.

Bettany: So that's autumn and spring?

Elizabeth: That's right. Now I'll just mark one point, place for you here. This is 1664 but it's actually an amendment of a 1662 list, so that's what's interesting because that tells you the changes between the two collections and you've got some lovely little pieces in here. No such person nor house to be found. And the next one, the house fallen down. Or if we try one of these comments up here, which says stopped up too. And this means that they didn't really want, they stopped up the chimney and therefore the hearth wasn't going to be used and therefore they wouldn't have to pay the two shillings. And in fact all sorts of people stopped them up.

Bettany: But was there a punishment if you didn't pay?

Elizabeth: Yes. They could distrain goods, which is rather like the modern bailiff, going in and taking some of your property which would be the value of the tax. There's another document here. Can I give you that top bit to hold. They curl up all the time.

Bettany: But presumably these are rolled up because they were much easier to transport.

Elizabeth: Oh yes. This is somebody who didn't pay. A Robert Aubrey and he was assessed for two hearths and refusing to pay the duty, distress was taken and he violently did oppose the constable and officer and did take away the distress. So the officer and the constable went to collect the money and he wouldn't give it, so they probably took a pewter plate or something, something that was equivalent to that value and then he'd go, no, I'm not going to give up my pewter plate, so he obviously hit them, I would think from this.

Bettany: So was it quite an unpopular tax?

Elizabeth: Oh yes, because every house had to be entered. And it's rather like the gas meter man coming in and saying I want to see in every room. We wouldn't like it now so they didn't like it then.

Bettany: Off to Cornwall now. The hearth tax lists don't give addresses but some Cornish enthusiasts have managed to connect the records with particular properties. I've arranged a rendezvous with one of them, Tom Arkell. We met at Pendine House which has been owned by the Borlais family since the 1630s.

Tom Arkell: This is the hearth tax list for 1662 and 1664 for St Just Parish. And the first name you find is John Borlais, or Burlase as it's written here. Seven hearths.

Bettany: And that would have meant that he'd have been taxed quite heavily then if you've got seven hearths.

Tom: Well, seven hearths at one shilling a hearth, twice a year, is 14 shillings which is a substantial sum of money, but he was a rich man. He made his money initially from tin mining and that's why he was able to buy this house.

Bettany: The records show that John Borlais paid his tax. But, as we know, some people went to great lengths to avoid it. Tom found an example of this at Bray Farm, now the home of Sutton Sailor and Michael Shepherd.

Bettany: So, Tom, do you know who owned this house in the 1660s?

Tom: Yes, we do, it was John Ellis and his name is down here on the copy of the hearth tax list. There, you see, John Ellis, six hearths, stopped up, two.

Bettany: I have to say this one looks pretty open to me. How do you know that this was one of the ones that was stopped up?

Michael Sheppard: Well, it's just a plain wall but it was damp and we were exploring the damp patch and discovered, firstly the surround and then the centre of the hearth was completely blocked with granite.

Bettany: That's extraordinary. So you'll have been the first people for 330 years to have seen it. You didn't realise you had an important bit of fiscal history in your bedroom. One thing that had impressed me about the hearth tax was the theory seemed fair. Rich people had more hearths and so would pay more. But the last stop in Cornwall questioned that. In 1662, Treen Farm was the home of James Carra. It had one hearth. James' sister, Marie, lived in the cottage next door. Also a one-hearth home. And presumably Marie would have been unmarried which is why she came to be living here.

Tom: Yes, she was. She was the sister of James next door.

Bettany: Well, she might have only had one hearth, but it's pretty impressive, isn't it.

Tom: It is, it's a big hearth for a small house.

Bettany: Despite the size of the hearth, Marie was very poor. Tom showed me a document that proved this.

Bettany: And so this has got a list of all the goods that Marie owned when she died. Was that one old suit of clothes? One small spit.

Tom: Worth five pence, which would have been here in this fireplace.

Bettany: And one bowl worth tuppence. And this is the brother, so you know exactly what he owned as well. He's doing much better, isn't he.

Tom: There's the total, £146.

Bettany: James has got a lot of goods. Marie has hardly got any. They've both got one hearth so they could be taxed the same amount. I mean that doesn't feel to me like a fair tax.

Tom: It isn't at this level. In Cornwall three out of every four houses only had one hearth.

Bettany: So why do you think it was abolished after 27 years?

Tom: Well, I think it's clear. William and Mary had just come to the throne and they were after popularity. It's a measure of cheap popularity for them.

Bettany: Whether it was a castle or a cottage, people didn't like having their homes entered. The state needed new solutions.

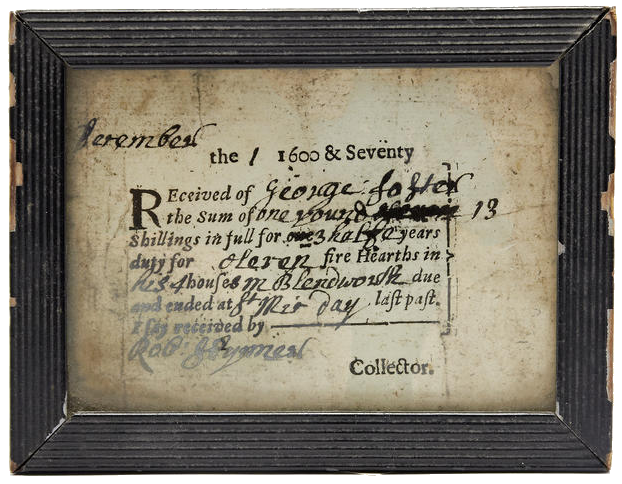

A Charles II printed and manuscript Hearth Tax receipt, dated 1st December 1670, covering the hiatus in collection from Michaelmas 1669 - Michaelmas 1670, later framed and under glass, 12.5cm wide x 9.5cm high including frame.

'December the 1 1600 & Seventy

Received of George Foster

the sum of one pound 13

shillings in full for 3 halfe years

duty for eleven fire hearths in

his 4 houses in Blendworth due

and ended at St Mic day last past.

I say received by

Robt Hymer [?]

Collector'.

This receipt reveals that George Foster of Blendworth, Hampshire, owned four houses with a combined total of eleven hearths. The surviving Hearth Tax Assessment for 1665 lists a George Foster of Blendworth as having two chargeable hearths; a Francis Foster of the same parish is liable for four, and a Widow Foster for three [see E. Hughes & P. White (eds.), The Hampshire Hearth Tax Assessment 1665 (1991).

The George Foster named on the receipt is probably the George Foster born in Blendworth in 1629 and whose will, proved in 1706, reveals that he was a yeoman with six daughters and a son, also called George.

The Hearth Tax was levied between 1662 and 1689 to support the Royal Household of King Charles II. It was levied on each householder according to the number of hearths in his or her dwelling. The tax comprised a twice-yearly (at Michaelmas [September 29th] and Lady Day [March 25th]) charge of 1s. for every fire, hearth and stove within each 'dwelling, or other house or edifice', in England and Wales, including lodgings and chambers in the Inns of Court and chancery, and colleges and other societies.

In March 1666, the government farmed out the tax to three City of London merchants following payment by them of an advance and an annual rent. This administration failed, largely because the rent had been fixed at a higher figure than the yield from the tax justified. The merchants surrendered the farm following the collection of Lady Day 1669. Whilst a report was compiled about how the Hearth Tax could be better administered, the collections of Michaelmas 1669 and Lady Day 1670 were outstanding.

This receipt, made in December 1670 by which time new receivers had been appointed, covering 'three half years' up to Michaelmas 1670, thus records the collection of those uncollected taxes from Lady Day 1669. No assessment survives for the county of Hampshire for the year and a half ending Michaelmas 1670.

This tax was widely hated, and regarded as a 'badge of slavery upon the whole people exposeing every mans house to be entred into and searched at pleasure by person unknown to him'. In the first session of the first parliament of William and Mary, which assembled on 13 February 1689, the Hearth Tax acts were repealed.

Lot 302 (£200 - 300), Auction 22670: The Oak Interior including the Collection of Roger Rosewell FSA of Yelford Manor, Oxfordshire [Lots 1 - 130], Bonhams 22nd January 2015 11:00 GMT