Just before dawn at 6 a.m. on 6th November 1917 the final assault and battle for the devastated ruins of the tiny village of Passchendaele began. The cold, dull but unusually rainless sky was lit up by the flashes from thousands of cannons and guns spewing their murderous barrage onto the German defenders sheltering in their trenches and fortified positions in and around Passchendaele.

By 7.15 a.m., in spite of heavy casualties inflicted by the grimly determined enemy, Canadian soldiers crossed the final 500 yards, captured the village, and were busily dealing with the remaining Germans.

Passchendaele was finally in Allied hands and the Battle of Third Ypres was drawing to its close. During the next few days and after further costly attacks, the surrounding ridge was subsequently taken until, on 10th November, this Battle officially ended. On 20th November the Flanders Campaign, having "served its purpose", was closed down.

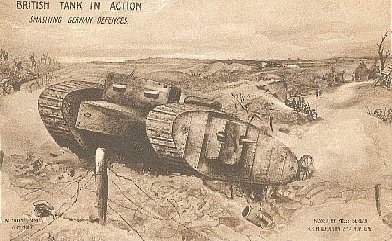

For another reason, also, the 20th is a significant date in the history of warfare. On that day 381 British tanks, re-using the seemingly forgotten tactic of surprise and, consequently, unheralded by the usual artillery barrage, rumbled out of the morning mist and attacked the Hindenburg Line near Cambrai. Initially this attack achieved the dream of every army commander on the Western Front and broke through the Enemy lines. However, this success was short-lived and the eventual gains there were slight.

|

|

| British Mark 5 Tank | British Mark 1 Tank |

The meaning of the word "purpose", referred to above, is very complex and has its origin in the causes and conduct of the Great War itself.

Causes

By the first decade of this century the ruling family dynasties of Europe were nearing their end. Variously founded over the preceding centuries by conquests, alliances, treaties, and marriages they were having great difficulties in coping with the intellectual hopes, economic desires, and political aspirations of their subject peoples. At the end of the Great War they had mostly disappeared - generally unregretted and unlamented.

In 1914 the ruling systems in the three formerly great autocracies of Austro-Hungary, Turkey, and Russia were especially brittle. Each, for several decades, had gone through traumatic periods of internal and external revolution, dissension, and upheaval.

All of them, because of internal feebleness, found not only that their influence abroad was declining, but in the cases of Austria and Turkey, that many of their once subject countries had gained, or were seeking to gain, independence from them. The most unsettled area of all was in the Balkans. Here many different races and peoples were trying to achieve their own self-rule by taking advantage of these weaknesses.

Russia, when oppression failed, saw an opportunity to deflect its own people's eyes from internal problems and eagerly embraced the cause of the Slavs. She sought to gain influence in Rumania - a strategy which caused alarm in Austria.

Austria was riven with racial discord. She tried to keep her subject states under control with military force and saw Serbia as the instigator of, and rallying point for, her disaffected Serbian and Croatian peoples. Austria was convinced that war with Serbia was necessary, not only to end Serbian influence outside her borders but also to subdue the racially dissatisfied elements within.

Germany, under the control and guidance of Bismarck, had only become a unified country in 1871. Then her military skills and Prussian army overwhelmed the French and made Germany the dominant military power in Europe. In seeking peace, France was forced to give up the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine to Germany. This was cause for continued embitterment by France and a perpetual desire for the return of these territories.

However, in 1888 William II ("Kaiser Bill") came to the throne. With his accession came a new force in German policy. Irritated by the restraints placed on him, William, calling Bismarck's bluff, accepted his proffered resignation when it was given in the early 1890s. With the "Iron Chancellor's" iron hand removed, Germany's foreign policy took a less predictable course under the guidance of the erratic and unstable William.

While in charge, Bismarck, knowing the simmering resentment in France, had allied Germany to Austria, insured a benevolent neutrality with Russia, and generally kept on good terms with Britain - especially if it encouraged suspicion of France. In doing this he managed to isolate France politically from the rest of Europe.

William, displaying his considerable talent for impetuosity and self-will, quickly antagonised the Tzar who, notwithstanding his dislike of republicanism, soon formed a military convention with France. Continuing on his way, William, with a bold contempt for Bismarck's policy, started to collect a colonial empire and, greatly to Britain's apprehension, a powerful navy with which to defend it. This apprehension was eventually translated into deed when Britain entered into the "Entente Cordiale" with France. This, in the end, led to a military understanding, and ultimately to the dispatch of the British Expeditionary Force to France at the outbreak of war.

Thus, by 1914, after many disputes, misunderstandings, shows of force, much petulance, and meddling, Europe stood divided into two hostile, bellicose, and suspicious camps. In the centre stood Germany tied to the flurries of a declining Austria; and on either side stood Britain, France, and Russia. With the Central Powers, Germany was by far the more powerful, but, as it transpired, the tail was to wag the dog.

The Spark and Touchpaper

On 28th June, 1914 the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to Franz Joseph and the Austrian throne, was murdered in Sarajevo, the Bosnian capital. The assassins - uncompromising Slav nationalists - were members of a secret society called the "Black Hand".

To Austrians, Franz Ferdinand was unpopular since he had dreams of a reconstructed empire held together, not in subjection, but in a federation of the various nationalities.

However, in spite of these ideals, he was regarded by the Bosnian Slavs as a symbol of Austrian oppression. Furthermore, they had no wish for a new confederation which, if it were successful, would destroy their hopes of independence and the chance of joining Serbia and creating a Yugo-Slav State.

Consequently, Franz Ferdinand was taking a great risk in Sarajevo. But the Austrian authorities there, having heard rumours of an assassination plot, were careless with, and seemed indifferent to, his security.

The first attempt on Franz Ferdinand's life failed, but with two gunshots, the second succeeded, and he died, prophetically, at 11 a.m..

The Fuse

In both Serbia and Austria there was ill-concealed pleasure about the assassination. The Serbians showed pleasure at the death of a hated foreigner, while the Austrians eagerly grasped the excuse to re-establish their own waning status by humbling Serbia with invasion and military conquest.

However, before such a satisfying and salutary solution could be undertaken, Austria had to ensure that she would be protected against Russia - the champion of the Slavs. The "tail" now quivering with anticipation was about to send its desperate tremors through its ally, Germany.

Consequently, at the end of June, Germany was asked if she were willing to safeguard Austria against Russia. The Kaiser was only too willing to oblige, and by the middle of July he opened Austria's unlimited adventure account.

Cashing in on this security, Austria delivered an ultimatum to Serbia on 23rd July. Its harsh terms were intended to be unacceptable, for, in effect, they demanded that Austria be given control over Serbian internal affairs.

Next day, Germany caused consternation in Russia, Great Britain, and France when it delivered notes to each, stating that the Austrian demands were fair and which also warned these Countries not to interfere in Austro-Serbian affairs.

Unexpectedly, Serbia acceded to most of the Austrian demands, and, on hearing this, the Kaiser, thinking that threats had been enough, was satisfied.

Too late! Momentum now controlled reason and the destinies of young men moved inexorably from the light into the shadow of death. A range of threats, proposals, understandings, notes, and reports all jumbled together and produced no solution.

The Explosion

At 11 a.m. on 28th July Austria pre-empted further negotiation and declared war on Serbia.

The generals of all the rival continental nations had their war plans, and military necessity and the mobilisation of armies now took precedence over the last hopes of politicians. On 31st both the Emperors of Russia and Austria ordered a mobilisation of all their respective armies. Germany started mobilising on 1st August.

The German war-plan, created and refined over many years, had the crucial concept that a war should be fought on two fronts at once - to the east in Russia and to the west in France. This plan could not be upset by the unhelpful non-belligerence of France. As a result an impossible ultimatum was delivered, and, while taking care not to offer provocation on her borders, France virtually ignored it. Still vacillating and anxious about England's attitude, the Kaiser was only persuaded to declare war on France on August 3rd.

The British Cabinet continued to waiver, but events just across the Channel speedily removed all doubt. On 4th August, as part of their long conceived master strategy, Germany invaded Belgium, and Britain - to honour "a scrap of paper" - was at war with Germany.

The generals had achieved war, and it took four years and millions of lives to prove that they could not achieve victory.

Armies and Strategies

Germany

The German army was created during the Napoleonic Wars and showed its true worth when, sixty or so years later, it convincingly defeated the poorly led and badly equipped French army in 1870. It was at the conclusion to this conflict that France yielded to Germany the Provinces of Alsace and Lorraine.

By 1914 the military system required every physically sound man to serve in the army. Each was conscripted and then trained in the regular army for up to three years. Once this was completed, part-time service was continued firstly in the regular reserves for up to five years, secondly in the Territorials (Landwehr) for twelve years, and finally in the Home Guard (Landsturm) up to the age of 45.

When the call to arms came, Germany, with its core of professional officers and highly trained and skilled NCOs, was able to field an army not only much larger than expected but also courageous, confident, and patriotic. As events were to reveal, it was well capable of taking offensive, decisive, and winning action.

Austria

Germany, both geographically and politically was at the centre of Europe. Its people were German-speaking and proud to belong to their country. Austro-Hungary, on the other hand, had a vast frontier and was composed of a polyglot collection of races - many of whom were mutually hostile, and unhappy at even belonging to a corrupt Austrian Empire.

Consequently, the positioning of troops within her borders was a more complicated matter than in Germany. Unless care was taken, soldiers stationed on one within the frontier might be racially similar and politically sympathetic to the hopes of those without.

While the Austrian Empire was in its twilight years, Germany was in the full strength of its powers. Austrian generals were tainted with this decline, and, only exceptionally did they approach the professionalism of the Germans. Austria, unable to forget her past glories and unwilling to concede her weakness, could not gladly accept the inevitable German direction of the War.

What does surprise, perhaps, is that she was able to withstand the successive shocks of war right up to the end in 1918.

Russia

As was illustrated in the Napoleonic Wars, and, to a hugely greater extent in the Second World War, Russia had two great assets in warfare - the vastness of her territories, and a mighty resource of manpower. Moreover, given a patriotic cause, her peoples - despite severe internal problems - had the will to fight with a courageous zeal and an unquenchable patriotism which was careless of death.

But in 1914 the army's leadership was riddled with corruption, and incompetence was rife throughout its whole structure. The ordinary soldiers were badly trained, there was a lack of weapons, and those which existed were mostly old fashioned and out-of-date. The capacity of her manufacturing industry was, for example, far below that of Germany and, because of very poor communications - especially railways - it was only with very great difficulty that men and material could be moved about the country. Compounding this problem, was the fact that in winter her northern ports were ice-bound and the waters to the ice-free ones to the south were controlled by her enemies. Consequently, during the War her allies found it very difficult to make good these serious shortages of equipment.

France

A problem of which France was acutely aware was that of the unfavourable disparity between her population of 40,000,000 and that of Germany with 65,000,000. This meant, in effect, that French potential man power for her armed forces was about six million, whereas that of Germany approached ten million.

To try to overcome this imbalance, France had a system of conscription into the army. Men were called up at the age of twenty when they served full-time for three years. Once this was completed they did a further eleven years in the Reserve, seven years in the Territorial Army, and finally seven years in the Territorial Reserve. This system gave the French command about one million first line fighting soldiers which, it was hoped, would be enough for the limited but decisive campaign for which their strategy called.

However, the French attitude to their reserves was very much different from that of the Germans. The former regarded these soldiers to be of very limited use and generally only fit to be stationed behind the line for defensive and garrison duties. To be classed so lowly only convinced the reserves that they were, in fact, second-rate soldiers. The tragedy was that the French considered the German reserves to be of the same quality as their own, and that, therefore, they would be used in the same fashion. That this was not the case came as a most disagreeable shock to the French high command once hostilities started.

The French general staff bore comparison with the German. Over the years since 1870 it had given much logical thought to the future strategy to be used in a war against Germany. In the final few years before 1914 it had come to the conclusion that morally and spiritually the French were superior to their former conquerors. Therefore, with right on their side, they must eventually break the fighting spirit of the Germans. As a result it had become the all pervading belief that victory would be achieved if enough attacks were made against the enemy.

High-minded and righteous as this policy may have been, it proved to be a disaster. A doubtful superiority of will counted for little against the determined and professional German army better equipped both with artillery and machine guns.

Great Britain

In all the four main opposing continental powers there was a close similarity of military system and purpose. On the other hand, Britain had for centuries a much different philosophy of warfare. She was at heart a sea power, using political influence and financial subsidies to support whichever country happened to be her ally. From time to time her small wholly professional army, perhaps always regarded with a hint of suspicion since the days of Cromwell, was used to give aid when the need was great. The army's main role was in the safeguarding of the Empire - in particular, India.

Although the army was small, generally neglected and poorly maintained, it did have, on the credit side, a wide experience of different types of fighting gained in local engagements all over the world. Against this knowledge, however, was the fact that this did not, in any way, prepare any British general for the handling of the vast armies later to be commanded in the Great War.

To protect its island position, the Empire, and the connecting shipping lanes, Britain maintained the largest navy in the world. While this went unchallenged Britain felt secure. But, from before the turn of the century, at least two factors had arisen which gave cause for concern, if not alarm.

Firstly, Germany had started to acquire its own empire, and, to protect it, she needed a navy comparable with that of Britain. Since Britain was the only nation at that time who had a powerful navy, it was seen in this country that a German navy could only be used to challenge this country's maritime supremacy. Secondly, with the passing of sail propulsion and wooden hulls, in favour of steam engines and iron-clad sides, the historic lead which Britain enjoyed at sea, quickly vanished with the ability of any industrial country to create a fleet in a short number of years.

War Plans

From the early winter of 1914 to March 1918 the war on the Western Front is best described as a siege with the Allies in battle after battle vainly attempting to break through the unyielding German lines. Advances were often measured in yards, and casualties in tens of thousands. Each commander's most desired ambition was to make an unstoppable penetration of his enemy's defences. But on those rare occasions when breaks were made, they always came to a halt because of the seemingly insurmountable task of widening and deepening them with fresh, reinforcing troops and supplies. To the generals at the beginning of the War this was a possibility hardly thought of and certainly not considered. There were several causes for this, but at heart the reasons lay in the failure of the rival plans of war.

Germany

The German war plan was basically dictated by the disparity in the combined populations of Germany and Austria and those of France and Russia. Germany realised that a war against France and Russia fought simultaneously on both fronts was almost certainly doomed. Consequently, it would be necessary to defeat one while holding the other in check. Remembering the example of Napoleon, the Germans reasoned that it was unwise to tackle Russia first of all, and risked being sucked into that vast, inhospitable interior while France was able to attack from the west. What was needed then was a swift, decisive victory against France. Once this was accomplished, Germany could then turn her attention to Russia, where, it was assumed, there would have only been a slow and protracted mobilisation.

Thus, the fundamental concept was conceived. Graf Schlieffen, chief of the German general staff from 1890 to 1905, gave it birth. Looking at the map of France, he came to the conclusion that the area of their common frontier from Switzerland to Thionville, south of Luxembourg, presented too great a hazard for invasion. Generally the region was crossed with difficult terrain, covered in thick forest, and defended by a continuous system of French fortresses such as those at Epinal, Belfort, and Verdun. The only possible gap, forty miles wide, lay between Toul and Epinal. However, Schlieffen considered this to be too narrow to allow a proper and overwhelming attack. Furthermore, it was only thinly defended, for the French had left it weak in the hope that it would act as a strategic trap through which the Germans would be drawn and ultimately destroyed.

Faced with this impasse to the west, Schlieffen turned his thoughts to Belgium and north-eastern France. Here the land was much flatter, and the gap between the English Channel and the Ardennes much wider, making it altogether very much more suitable for the task he had in mind.

Eventually he settled on his plan. Firstly, he allocated ten divisions to the east to hold the Russians at bay. Secondly, ten divisions were allotted to the Rhine area where they were to absorb the strength and bend before the expected French main offensive. Finally, fifty-three divisions were to make the decisive invasion through Belgium. With the violation of Belgium neutrality, he took into consideration his belief that Britain would enter into the war against Germany - having the capacity, at first, to put 100,000 men into the field.

His strategy showed boldness, imagination, and subtlety. He hoped that within a month the armies invading through Belgium would have reached a line roughly stretching from the English Channel at Abbeville to its pivotal point near Metz. This meant that the western flank, in advancing more than 200 miles, would have to conquer the Belgian army, overwhelm the man-made fortresses at such towns as Namur and Liege, and cross the natural barriers of rivers like the Meuse.

As a conclusion to this advance, the armies were to swing south of Paris and then turn east to fall upon the French armies from the rear. This is where his plan showed its subtlety. It was expected that by far the strongest French attack would be eastwards across the Rhine. To make this possible the French, logically believing that the Germans would not attack through Belgium, concentrated most of their soldiers in the east. Once the ten German divisions stationed there contained these thrusts, it was only a matter of time before the armies advancing from Belgium, crushed the French against the Swiss border and the mountain fortresses of Lorraine. The more men which the French kept from the north in order to push their offensive to the east, so the task of the Germans became more likely to succeed.

To Schlieffen the success of his entire plan depended upon the speed, strength, and direction of the German right wing and its southern sweep around Paris. But as so often happened in the Great War, plans and dreams ever yielded to remorseless necessity and merciless reality.

France

For more than three decades after the humiliation of 1870, French strategy planned for a defensive holding operation based upon the eastern frontier fortresses followed by an offensive attack eastwards into Germany.

However, during the ten years up to 1914 a new school of thought gained control of military thinking. This propounded that, given French dash and modern mobile artillery, all-out-attack ("offensive à outrance") guaranteed success in modern war.

A belief that courage alone could ignore bullets and make light of shells was bad enough. But the error of this misconception was further compounded by a false strategy which manifested itself in two very grave miscalculations at the heart of the infamous Plan 17

Firstly, it greatly underestimated the numbers of men which the Germans could put into their initial attack in the west. In creating this Plan it was considered that the most number of divisions which the Germans could assemble was about seventy. At the start of hostilities French Intelligence calculated that there were only about forty five in the field. However, both were wrong to a considerable extent, for, when the reserves were added in, the German divisions totalled over eighty.

Secondly, and even more serious, was the mistaken belief that the main attack would come, obligingly, through the Ardennes. This would then allow the French to sever German communications while at the same time making an overpowering all-out assault eastwards into Lorraine towards the Rhine. A very unwise decision. Even if the German numbers had been as small as the French estimated, it would have meant an assault against a heavily defended region in difficult country with, at best, roughly equal forces. Events were to show that this was a certain recipe for failure. Moreover, by thrusting through Lorraine and keeping the very great majority of their soldiers in the east, the French played into German hands and made the invasion through Belgium that more easy to accomplish.

Finally, in concentrating their armies in the easterly fortified country, the French confined themselves to a zone against which they could be attacked and eventually crushed from behind by the main German advance.

Great Britain

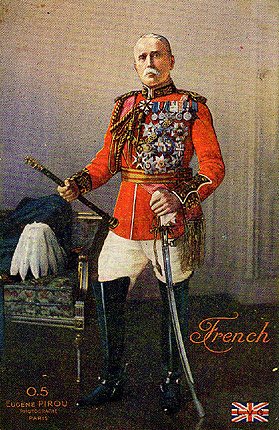

From 1905 to 1914 the general staffs of Britain and France held discussions about the role of Britain in a European war against Germany. During these years Britain's traditional policy in times of war of relying for protection mainly on her navy was gradually eroded. The general staff, influenced by the persistent advocacy of Henry Wilson, yielded to a more "continental" way of thought. As a result the Army was ultimately committed to fighting in France on the left wing of the French armies. Lord Kitchener - the War Minister, Sir John French - the designated Army Commander, and Douglas Haig all had their reservations about this plan, but by 1914 it was too late to change.

Thus by August 17th the bulk of the British Expeditionary Force had landed in France. The operation had gone so smoothly and secretly that the Germans had no knowledge of its presence.

Men and Arms

Darkness settled, the stage was set, and the curtain was about to rise. This sinister shroud would only fall and the arena finally close when the audience had wearied of death and the actors were too exhausted to continue. But what sort of actors were they and how well were they trained ? How extensive was their repertoire and how well had they learned their parts ? How well were they directed and how well had the props been prepared ?

Today, when the strategies and tactics of generals and the dealings of politicians are usually the substance of partisan debate, what still fascinates is the part played in the Great War by ordinary civilians hurriedly transformed into soldiers and plunged into a struggle which they barely understood. It is difficult, if not impossible, to comprehend how they withstood the traumas, fatigue, filth, terror, and boredom so resolutely for so long.

This is not to say that the generals who led them had a much clearer idea of how, initially, to wage and, finally, to win a war which was unlike anything they knew and was far beyond their experience.

In 1914 no British general had any experience whatsoever in the handling of large armies. Indeed Britain, when compared with the major continental powers, had never had a large army. Such soldiers as there were had been used exclusively to patrol and control the trouble spots of the Empire.

Promotion came with length of service and, consequently, officers tended to be restricted in outlook, unreceptive to new techniques, and wary of novelty and innovation. Moreover, senior commanders were often at least middle aged, and frequently in ill health. When he led the BEF to France Sir John French was 62. He had recently suffered a severe heart attack and had been ordered by his doctors to take life as easily as possible. Murray, who was French's Chief of Staff, collapsed early on at the Battle of Le Cateau, and never really recovered. Grierson, who went out to command the II Corps, had a fondness for good food and a dislike of physical activity. He died on the way to France at the age of 55. However, not all were like this, and Haig - the other Corps Commander was, at 53, exceptionally fit and in very good health.

Relationships amongst the generals themselves was often not good, and one or two examples should be enough to give a feeling for the atmosphere which prevailed. Haig told Charteris (his future chief intelligence officer) that he, Haig, considered French not only to be "quite unfit for high command in time of crisis", but also obstinate and unable to accept advice. He also thought Henry Wilson to be much more a politician than a soldier - and to Haig a politician was little better than a crook. The infantry man Smith-Dorrien took command of the II Corps after Grierson's death. Until his controversial dismissal after the German attack on Ypres in 1915, Smith-Dorrien was regarded with suspicion by French, the cavalry man.

To most British generals the cavalry was the paramount branch of the army. Ignoring, or unaware of, the indications presented by the Boer War and Russo/Japanese War that gallant, dashing horsemen were no match for bullets, they convinced themselves that it was this section of the army which would finally exploit a break-through and bring decisive victory. Given the deadly fire of machine guns, the concentration of artillery, and the chaotic state of the land which the explosions of shells left, the cavalry proved completely ineffective. Not only were they generally ineffective, but the upkeep of so many of these, often unused, soldiers behind the lines and, for example, the supply of forage alone took up many valuable resources which would have been better used elsewhere.

By 1914 Britain was, like Germany, a wealthy nation with many powerful industries easily capable of mass-producing weapons of mass destruction. During the War tanks, gas, hand grenades, trench mortars, flame throwers, and aeroplanes came into common use, and sometimes, together or separately, brought about decisive tactical results. Other, more established weapons such as machine guns and artillery pieces, were manufactured in vast quantities.

But the British army took up many of these only reluctantly. Encouraged by French élan, the generals felt that the rifle and bayonet were the true infantryman's weapons. It was considered that few troops could withstand the high rate of a British professional soldier's rifle fire and the subsequent charge made with the cold, sharp steel. In the event bayonets, being too awkward, were seldom used in man-to-man trench combat. More favoured were knobkerries, nail-studded maces, and hand grenades - all of which were more effective in the close confines of trenches.

What was not realised, at first, was that a few, well-entrenched machine guns could slow down and quickly halt an attack made by very much superior numbers. It was only later in the War, when the deadly potential of this weapon was realised, that British battalions were equipped with anything like an adequate supply of both light and heavy machine guns.

In the early stages both hand grenades and trench mortars were in short supply. Soldiers sometimes made their own, with results which were, not infrequently, more hazardous to the dispatchers than to the intended victims.

In Britain before the War one or two prophets foresaw the murderous potential of machine guns. What was needed, they thought, to counteract this menace was some form of armoured and mobile land ship. From this farsightedness the tank was born. The birth was difficult for few generals believed that such an instrument of war was necessary. It was only with great tenacity of purpose that its protagonists managed to get the first few created. However, by 1916 some were ready and commanders then realised that these awesome machines offered some form of hope in overcoming the carnage which had been produced by the stalemate of trench warfare. Those who had nurtured this new attacking arm had clear views on how it should be used. But, greatly to their disappointment and apprehension for its success, their opinions went unheeded and were discounted for the sake of expediency.