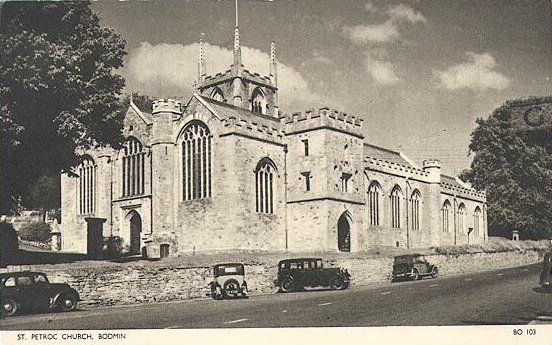

King Arthur and St. Petroc's Church, Bodmin

See also The Arthurian Legend

St. Pedrog, Abbot of Lanwethinoc (circa 468 to 564)

(Latin - Petrocus, English - Petrock)

Feast day: 4th JuneThe name Pedrog is probably a variant of modern Patrick. Petroc, as he is generally known in Cornwall where he is patron saint, was a younger son of King Glywys Cernyw of Glywysing. He may be identical to, or confused with, the legendary King Petroc Baladrddellt (Splintered Spear) of Cerniw. Upon his father's death, the people of Glywysing called for Pedrog to take on the crown of one the country's sub-divisions like his brothers. Petroc, however wished to pursue a religious life and left, with several followers, to study in Ireland.

Petroc and his band eventually returned to Britain landing at Hayle on the shores of the River Camel in Cerniw (Cornwall). He may have gone on a further pilgrimage to Ynys Enlli (Bardsey), founding churches at St. Petrox (Dyfed) and Llanbedrog (Lleyn) on the way. They were directed, by St. Samson, to the hermitage of St. Wethnoc who, seeing Petroc's superior piety, agreed to give him his cell in return for Petroc naming the place Llanwethinoc (now Padstow - Petroc's Stow) in his honour. Petroc founded a monastery on the site.

Back in Cerniw, with the help of Saints Wethnoc and Samson, he defeated a mighty serpent which the late King Teudar of Penwith had used to devour his enemies. This done, he departed from his monastery at Llanwethinoc (Padstow on the north coast) to live as a hermit in the woods not far away at Nanceventon (Little Petherick). Some of his fellow monks followed his example at Vallis Fontis (St. Petroc Minor). Petroc took to living as a hermit on the wilds of Bodmin Moor and it was while in the wilderness that a hunted deer sought shelter in St. Petroc's cell. Petroc protected it from the hungry grasp of King Constantine of Dumnonia and managed to convert him to Christianity into the bargain.

After thirty years there, he decided to go on a pilgrimage to Rome, via Brittany. On his return journey, just as he reached Newton St. Petrock (Devon), it began to rain. Petroc predicted that this would soon stop, but it continued to rain for three days. In penance for such presumption, Petroc returned to Rome, travelled on to Jerusalem and finally settled in India where he lived for seven years on an island in the Indian Ocean.

He then returned to Cornwall (with a wolf companion he had met in India), built a chapel at Little Petherick near Padstow, established a community of his followers, and then became a hermit at Bodmir Moor, where he again attracted followers and was known for his miracles. Petroc later moved still deeper into the Cornish countryside, where he discovered St. Guron living in a humble cell. Guron gave up his hermitage and moved south, allowing Petroc, with the backing of King Constantine, to establish a second monastery called Bothmena (Bodmin - the Abode of Monks) after the monks who lived there. When visiting some of his disciples Petroc eventually died at Treravel, while travelling between Nanceventon (Little Petherick) and Llanwethinoc (Padstow), and was buried at Padstow. The monks there later removed themselves, along with Petroc's body, to Bodmin where his beautiful Norman casket reliquary can still be seen today.

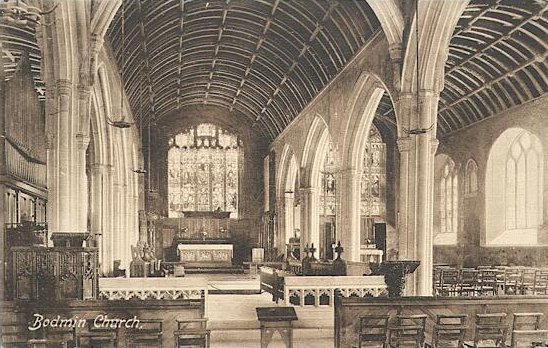

The cult of St. Petroc became widespread in Devon and Cornwall, in South Wales and in Brittany, even becoming recognised in Italy. His relics became the object of an undignified push-me-pull-you between Cornwall and Brittany: initially at Bodmin, they were secreted out of the country in 1177 and it required the intervention of King Henry II to get them returned. In reparation, William, Bishop of Coutances, presented to the Cornish people a fine ivory reliquary: it was hidden at the Reformation, rediscovered in the 19th century, and survives, a remarkable example of medieval art, in Bodmin church.

King Arthur

The battle to prove that King Arthur had an existence prior to Geoffrey of Monmouth's monumental work, History of the Kings of Britain, has been fought, over the years, by many different soldiers using many different weapons. Geoffrey has been given credit for (or accused of) single-handedly creating the legend of King Arthur out of thin air. While it is not necessarily the case that his 'History' is a work of pure fiction, in the absence of any concrete support for Arthur's existence, much effort has been spent on finding clues that predate Geoffrey. In addition to providing fuel for the true believers' fires, any such finds would tend to vindicate Geoffrey (at least a little bit), in the process.

The rules of this scholarly game require that:

"before anything can be entered into evidence for the existence of a historical King Arthur, it must be reliably dated before 1136 (the date of publication of Geoffrey of Monmouth's 'History'). Anything after that date, no matter how compelling, well attested or far removed in time and space, is considered, by the entrenched scholarly communities who decide these things, invalid and inadmissible, due to Geoffrey's all-pervasive influence after publication of the 'History'.

It may not be fair, but those are the rules.

One tantalizing bit of evidence, that does indeed appear to predate Geoffrey, comes to us from a chronicle, written in 1146 by one Hermann of Tournai. Its Latin title is 'De Miraculis S. Marie Laudunensis' or, in English, 'On the Miracles of Our Lady of Laon'. In the chronicle, Hermann relates certain events that took place in the year 1113. The story goes something like this: a group of nine canons from the church at Laon, France, went on a fund-raising trip to England, taking with them the Shrine of Our Lady of Laon, a collection of miracle-working relics. Their cathedral church had burned down and it was their hope to travel around the country, visiting as many places as their time would allow and to raise money for rebuilding their church, in payment for the "cures and healings" that they said their relics could produce.

In their travels, they visited the town of Bodmin in Cornwall. They were told that they were in the 'Lands of King Arthur' and were shown various local sites that were associated with him, such as Arthur's Chair and Arthur's Oven (the fact that there were topographic features named after Arthur also seems to be an indication of a rather strong local Arthurian tradition).

While there, a man with a withered arm came to them looking to be healed of his affliction. In the course of conversation with the man, he said that Arthur still lived. Members of the visiting group from France apparently mocked him for saying such a nonsensical thing. The crowd of onlookers, though, supported the man's contention and a brawl broke out, which required armed force to stop.

So what ? The point, here, is that it may very well be, if Hermann of Tournai is to be believed, that prior to Geoffrey of Monmouth's writing of the 'History of the Kings of Britain' there was a generally held belief, at least in Bodmin, Cornwall, that Arthur was not only a genuine historical figure, but that he was still alive in 1113.

Does that prove Arthur's existence ? Not at all. But slender threads like these become lifelines to the credulous. Another such lifeline is the famous 'Modena Archivolt'. And, if true, it would prove that their credulity is founded on more that just Geoffrey of Monmouth's imagination. The abduction of Guinevere is a very popular element of the Arthurian legend, first appearing in written form in Caradoc of Llancarvan's early 12th century 'Vita Gildae' (Life of Gildas), throughout the Arthurian Romances of the late 12th century, through Ulrich von Zatzikhoven's 'Lanzelet', Chrétien de Troyes' 'The Knight of the Cart', up to Malory's definitive account in 'Le Morte d'Arthur'. Evidence of this tradition can be seen in an early 12th sculpture at Modena cathedral in Italy, on which in 1099 a group of sculptors began work. The north portal of Modena Cathedral, known as the Porta della Pescheria, features a high relief carving in the marble archivolt depicting a scene from the tale of the abduction of Arthur's Queen. The Arthurian sculpture on the Modena archivolt is seen as evidence that an independent oral account of the tale of the abduction of Guinevere was known in Europe prior to the writings of Caradoc of Llancarvan and Geoffrey of Monmouth.

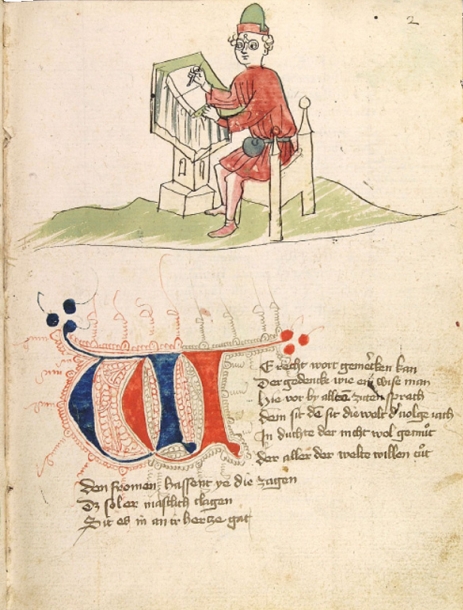

Ulrich von Zatzikhoven and the first lines of Lanzelet in the Manuscript of HeidelbergWhat does all this have to do with St. Petroc's Church in Bodmin ? Just this. If the Laon Canons were visiting anywhere in Bodmin, Cornwall, they would have visited the local monastic community or the local parish church - and, it so happens that St. Petroc's is both. John Leland, in 1533, visited Bodmin and said:

"The former Augustinian priory, whose patron and sometime resident was St. Petroc, lay in the churchyard of Bodmin parish church, at the east end. There have been monks, then nuns, then secular priests, then monks again, and finally regular canons in St. Petroc's church, Bodmin."

Present day St. Petroc's parish church, is on the site that the Laon Canons would have visited. On the east side of the property stands a ruined church. It is possible that in that very building, the event recorded by Hermann of Tournai over 850 years ago, the brawl over a belief in King Arthur, actually took place. If so, then St. Petroc's plays an important role in the Arthurian story.

Copyright © David Ramsdale 1997 - 2021

All rights reserved