Part 1 Index: Etymological & Teutonic Sources

- Derivation of the Surname RAMSDALE

- Etymology

- Teutonic Sources

- Viking Influence

- Danish or Norwegian Origin ?

- Topographical and Habitation Surnames

- Heraldry

- Bibliography

- Møre og Romsdal, Norway

- Romsdal to Ramsdale

Part 2 Index: Locative Sources

- Ramsdale Hamlet, Fylingdales Parish, North Yorkshire

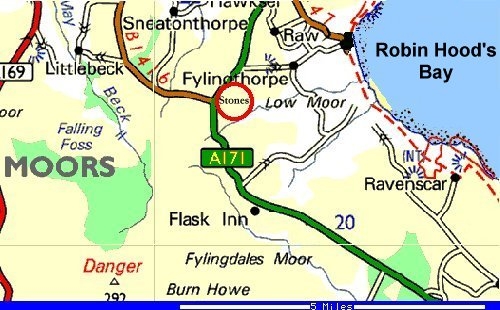

- Ramsdale Megalithic Standing Stones, North Yorkshire

- Ramsdale Valley, Scarborough, North Yorkshire

- Ramsdale & Ramsdell Chapelries, Hampshire

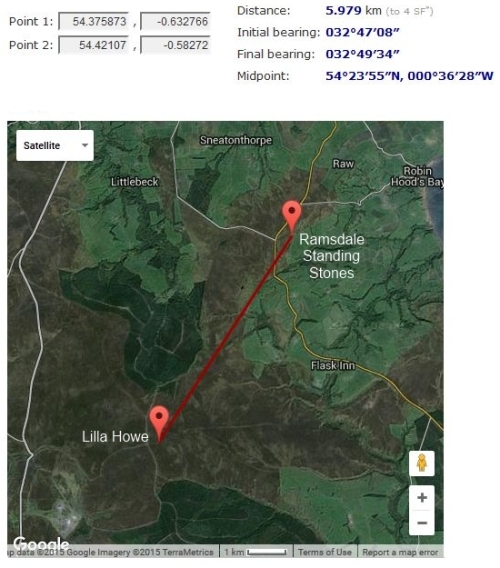

- Lilla Howe Bronze Age Barrow, North Yorkshire

- Cuerdale Hoard, Preston, Lancashire

- Wade's Causeway, North Yorkshire

Part 3 Index: Danish or Norwegian Origin

- Danish or Norwegian Origin (published sources)

- Danish or Norwegian Origin (table of place-names)

- Viking Society Web Publications

- Molde Wind Roses

- "On dalr and holmr in the place-names of Britain", Dr. Gillian Fellows-Jensen

- "The Place-Names of the North Riding of Yorkshire" (1979) A. H. Smith, Volume V

Part 4 Index: General

- Fylingdales: Geographical and Historical Information (1890), Transcript of the entry for the Post Office, Professions and Trades in Bulmer's Directory of 1890

- Fylingdales Parish: Victoria County History (1923) A History of the County of York North Riding Volume 2, Pages 534 to 537

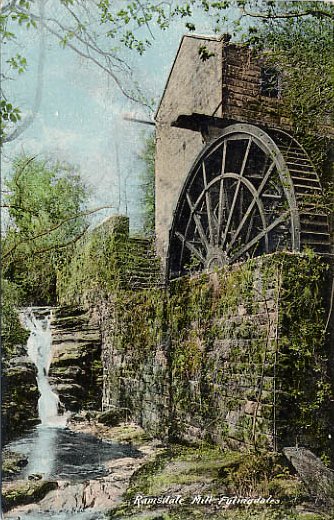

- Ramsdale Mill, Robin Hood's Bay, Yorkshire - Postcard Views (circa 1917 to 1958)

- Ramsdale Valley, Scarborough, North Yorkshire: Edwardian Postcards (1901 to 1915)

- Scarborough, North Yorkshire: Bulmer's History and Directory of North Yorkshire (1890)

- Ramsdale Megalithic Standing Stones, Bronze Age Stone Circle, Fylingdales Moor, North Yorkshire

- Robin Hood's Bay - published articles regarding its origin

- Ramsdale Family Register - Home Page

- Whitby Jet - published articles

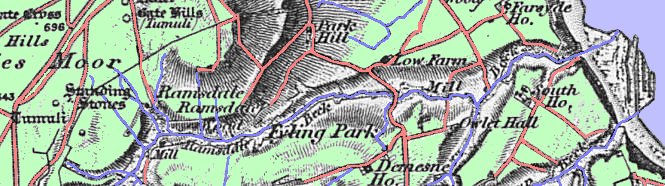

Ramsdale Hamlet, Fylingdales Parish, North Yorkshire

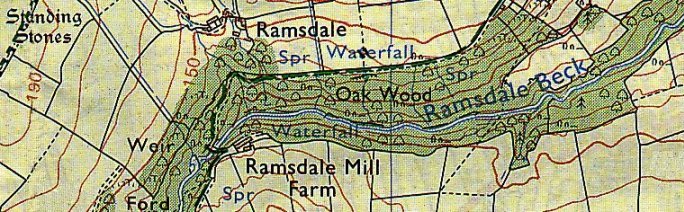

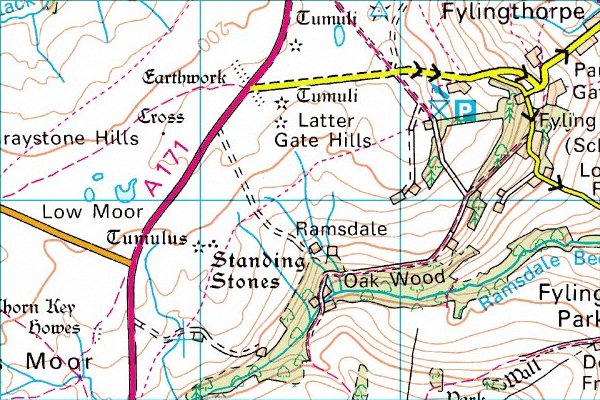

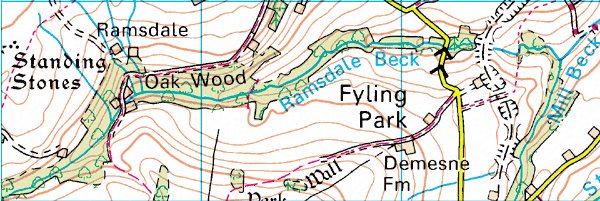

The most probable source of the surname is Ramsdale Hamlet in Fylingdales Parish, North Yorkshire [NZ 92722 03762] - Figclinge (11th century); Figelinge, Fielinge (11-12th centuries); ?Saxeby (12th century). This parochial chapelry lies south of Whitby parish and contains the villages of Robin Hood's Bay and Thorpe, or Fyling Thorpe (Presterthorpe, 13th century,) and the hamlets of Normanby, Parkgate, Ramsdale, Raw (Fyling Rawe, 16th century), and Stoupe Brow.

The abbot's park is mentioned in 1804, the woods of Middlewood, Ramsdale and "Marchescow" in 1240, when the abbot granted Richard de Fyling estover in the last two and pasture in the first (Feet of F. Yorks. 24 Hen. III, No 124). Ascending the hill to the south, Fyling (new) Hall, Park Hill, the former residence of Mr John Warren Barry, J.P., High Park Wood and Ramsdale Wood and mill are reached. Ramsdale Water-mill was stated in the 17th century to have belonged to Whitby Abbey (Pat. 10 Jas. I, pt xxv).

There are three waterfalls here, the highest (Stevenson's Piece) about 14 ft. Ramsdale Beck rises on Kirk Moor and as Leith Rigg Beck flows through Leith Rigg Wood, then as Ramsdale Beck descends through Ramsdale and Low Park Woods, to the south of which are Fyling Park and the hamlet of Ramsdale. From Thorpe Middlewood Lane goes south past the old Middlewood Farm to Mill Beck, which enters the sea south of Robin Hood's Bay and has at its mouth a mill, rebuilt, according to the inscription, in 1839.

| Stevenson's Piece Drop: 8 feet Location: Ramsdale Beck Grid Reference: NZ923032 |

|

This small waterfall is found near to Oak Wood just west of Robin Hood's Bay. To visit it plan a walk setting out from Robin Hood's Bay, then to Fylingthorpe and Fyling Hall School before following a path into High Park Wood which eventually leads to Oak Wood and Ramsdale Mill Farm. The waterfall is close by now so seek it out before returning to Robin Hood's Bay via paths through Fyling Park and to Boggle Hole, then coast it back to the start. |

| Ramsdale Mill Drop: 8 feet Location: Ramsdale Beck Grid Reference: NZ926034 |

|

Do the walk described above to visit Ramsdale Mill and see this quaint waterfall. Soon after the waters of Ramsdale Beck pass Ramsdale Mill the beck is met by a smaller watercourse near Mill Beck Farm to become Mill Beck. Mill Beck doesn't travel for long, it is less than one kilometre in length as it is shortly ended by its arrival at the North Sea at Boggle Hole. |

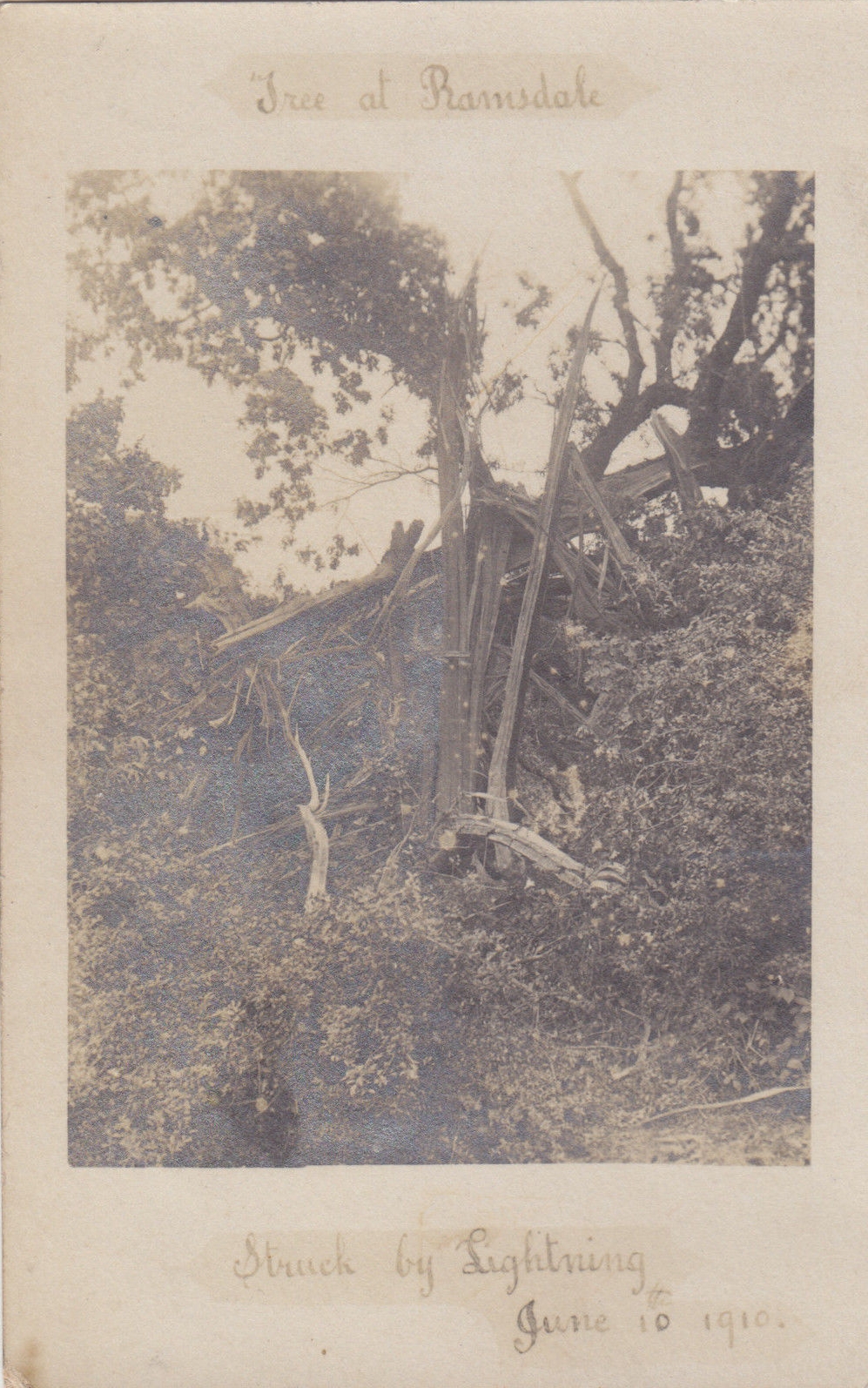

Tree at Ramsdale

Struck by Lightning

June 10th 1910

Ramsdale Waterfall, Robin Hood's Bay

Ramsdale Beck (waterfall) below Ramsdale Mill

Ramsdale Mill Farm (postally used 1921)

On Easter Monday, 12 April 1993 I visited Ramsdale hamlet, beck and woods. The weather was overcast and very misty. I traced Ramsdale beck, Ramsdale woods and Ramsdale mill farm which was unnamed (but identifiable by its solitary location) and very dilapidated. Unfortunately, I did not have time to visit what remains of Ramsdale hamlet which, from the map, appears to be only two or three closely spaced houses with access only down a long track.

Ramsdale Mill Farm Fylingdales North Yorkshire YO22 4QN Tel: 01947 880446 & 07989 340392 Cottage@ramsdalemillfarm.co.uk |

Set along a mile long country track, in the very heart of the North York Moors National Park, this attractive cottage offers an idyllic base for a walking holiday or romantic break. Adjoining the owners' home, it lies surrounded by ancient woodland with river flowing through, and footpaths winding amid wild flowers and open countryside. Robin Hood's Bay 3 miles is a maze of picturesque cobbled streets and 18th-century cottages leading down to the sandy beach. North York Moors Steam Railway at Grosmont 8 miles. Cliff-top golf course at Whitby 7 miles. Scarborough 15 miles. Inns and restaurants 1½ miles. External stone staircase to first floor entrance: Open-plan beamed living room with open fire, rugs on wooden floor, well-fitted kitchen/dining area and double bedroom with vaulted beamed ceiling. Ladder access to galleried twin-bedded room (for +2) with low sloping ceiling. Shower room/w. c. |

View Larger Map |

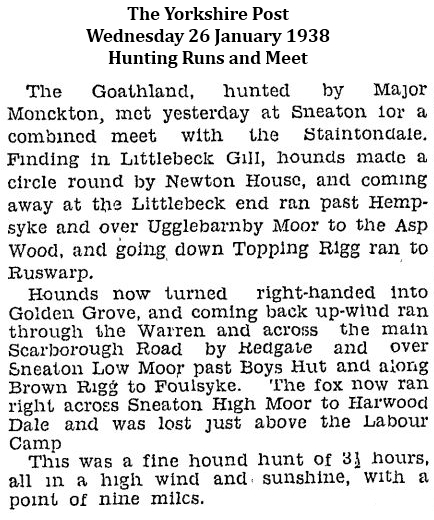

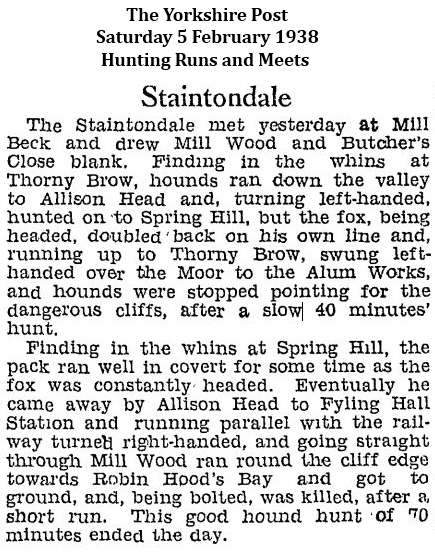

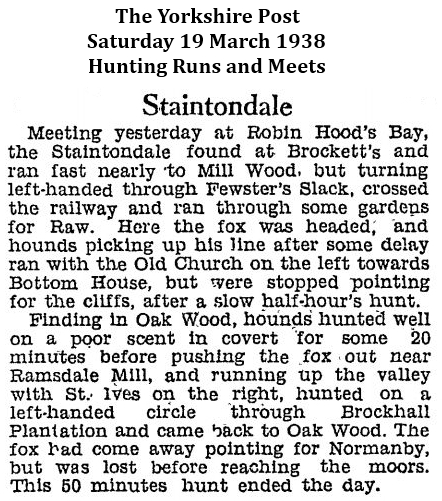

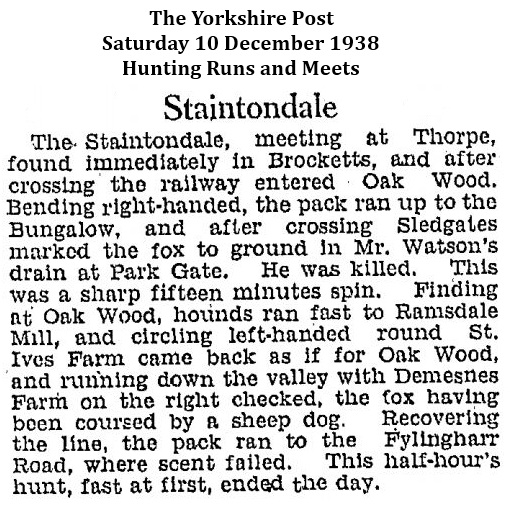

References to Ramsdale, Ramsdale Mill, Ramsdale (Oak) Wood and Ramsdale Beck

extracted from the hunting columns of The Yorkshire Post (1933 to 1939)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Yorkshire Post, Monday 17 April 1933 at page 8

Easter Outing of Naturalists

Yorkshire Union Field Day on East Coast

Robin Hood's Bay

Excursion to Kirk Moor and Foulsyke

Robin Hood's Bay, Sunday

The Yorkshire Naturalists' Union held their first field meeting of the year here yesterday, when a party numbering between 30 and 40, with headquarters at the Victoria Hotel, were favoured with ideal weather.

The bay in sunshine is a glorious sight, and the surrounding districts afford unlimited scope for students of nature. It is still early for plant life, but the advanced conditions of many ol the common flowering plants occasioned some surprise. The party found fine displays of stitchwort, wood sorrel, tuberous bitter vetch and anemones.

It is also early m the year for the migrant birds, and few species were seen. The first excursion took the members to Kirk Moor and Foulsyke, traversing on the journey the wooded slopes of Ramsdale Beck. This proved to be interesting ground for species of the lower plants partial to semi-aquatic conditions, and several of the rarer mosses were found, among which was Tetraph Browmana.

At Foulsyke the sweet gale was seen, and the beautiful catkins of the plant are at their best This is the herb from which gale beer is made by the local inhabitants, from recipes that have been handed down from generation to generation.

Ants and Beetles

The male flowers of the crowberry were also recorded. An unexpected entomological feature of Foulsyke was the prevalence of at least two species of ants which are found in very damp situations among the bog mosses.

A dead sheep furnished a beetle collector with specimens of several species. Very few stone flies were seen, although many may have been expected, and the stream itself, on the whole, was found not rich in normal life. In Raw Pasture Beck a water shrew was observed poking about the stones in the bed of a stream.

Interest was aroused by an object described as fossil fruit which had been found in the garden of one of the naturalists, and which on closer inspection proved to be an ironstone nodule.

Use is being made of the Marine Biology laboratory of the Leeds University in connection with the excursion. There was a representative body of naturalists present, among whom were the president, Mr. J. M. Brown, of Sheffield, Mr. F. Stamforth, of Hull, and Mr. F. A. Mason, of Leeds. A local lady naturalist, Miss Lucas, acted as guide for the excursion.

Click here to view the particulars of sale for Ramsdale House (10 April 2014).

Scarborough 966 - 1966 (1966) Mervyn Edwards (ed.), Scarborough and District Archaeological Society, Research Report No. 6 at pages 29, 34 & 35

Scarborough 1166 - 1266

(In 1210) … King John leased the burgesses the tenancy of the Falsgrave manor, its Ramsdale mill and demesnes [1].

Scarborough 1266 - 1366

Outside the walls, the burgesses gained full control of the manor of Falsgrave, which now came under their lordship. Within a few years they built two new mills in Ramsdale, after buying out John of Falgrave's rights in the ponds, there and in Burtondale. John was later able to claim that the mill-dam built by Roger Ughtred had flooded and destroyed his Falsgrave turbary. The first of the town's windmills was also built, on Bracken Hill (Gallows Close), subsequently known as the Windmill Leas. The sixty acres of demesnes land which the King had earlier let on a seven year lease to Roger Haldane, were recovered and re-let to the Commonalty of the borough. Besides the four acre manor site called King's Close, they embraced 159 strips, intermingled with those of other owners, in flatts at Colcliffe, Northleas and Greengate near Northstead; in Howe Field, Bracken Hill, Ramsdale, Falskarche and Quarrel Neb Fields, in Burtondale, below Weaponness and in the South Field.

[1] In 1210 King John gave 60 acres of Falsgrave Manor to Scarborough, along with its Ramsdale mill and common pasture rights. This meant that Scarborough had its own arable land and no longer had to rely on trade with its neighbours for barley and wheat. In a reversal of the relationship implied in the Domesday report of 1086 (which seems, by omission, to have considered Scarborough a part of Falsgrave manor), Falsgrave was now a part of Scarborough.

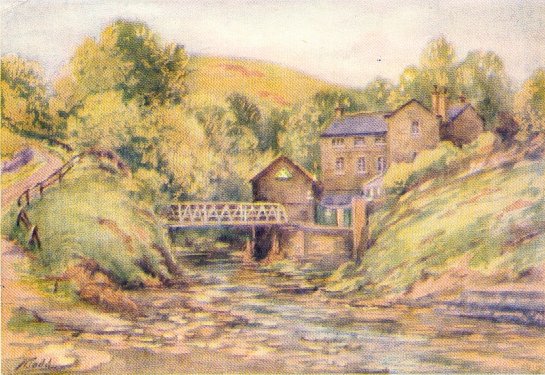

"Ramsdale Mill and House, Scarborough"

Joseph Newington Carter (1835 to 1871) watercolour, signed and dated '61, 19cm x 27cm

(before Valley Bridge was erected in 1861)

Ordnance Survey, First Edition

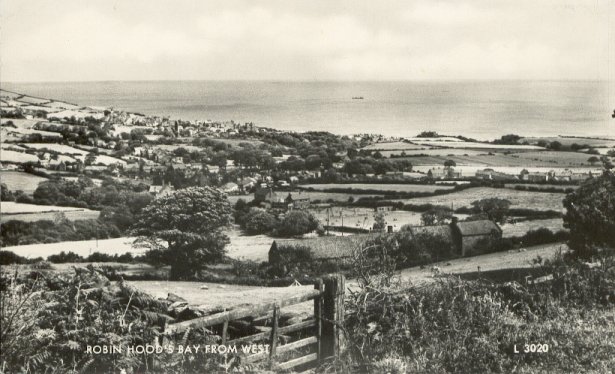

Robin Hood's Bay from West

Ramsdale Hamlet, Beck, Mill, Woods & Stones

Ramsdale woods are privately owned. The track through the woods is almost a road and, although very wet with numerous streams and springs, a four wheel drive vehicle could be driven along its length to Ramsdale mill farm and beyond.

Ramsdale Mill

Ramsdale beck crosses the track at Ramsdale mill farm and is very scenic. The beck falls sharply through a series of waterfalls and rapids down a steep narrow gorge lined on both sides by Ramsons (wild garlic) which completely cover the beck's banks up and down stream. It is likely that the river and woods (Oak Wood, formerly called Ramsdale Wood) take their name from this wild plant as it is the dominant plant life in the woods - Ramsons are considered to be an Ancient Woodland Indicator (AWI) species [5]. An unnamed house occupies the hairpin bend in the track which crosses, via a stone bridge, Ramsdale beck. The house appears to be occupied but is small and serves no apparent purpose despite its close proximity to the beck. This house and Ramsdale Mill Farm are the only two buildings in the woods at this remote location. Ramsdale Beck joins and becomes Mill Beck and enters Robin Hood's Bay at Boggle Hole (a "Boggle" is a hobgoblin which were thought to live in caves along the coast.)

[5] Allium ursinum is an indicator species for ancient woodlands in North Yorkshire categorised as "wet" and "neutral to calcareous".

Ramsdale Mill

| Transcript of the entry of "professions and trades" for ROBIN HOOD'S BAY in Pigot's Directory of 1834. |

| Shopkeepers, Traders, &c., |

| Leadsom William, miller, Ramsdale mill |

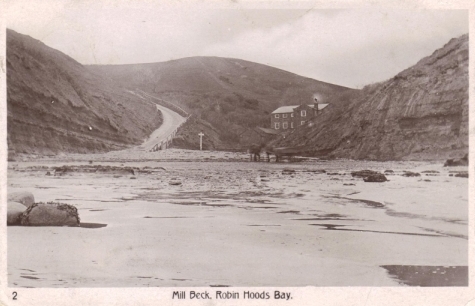

Mill (Ramsdale) Beck and Mill Farm at Boggle Hole, Robin Hood's Bay

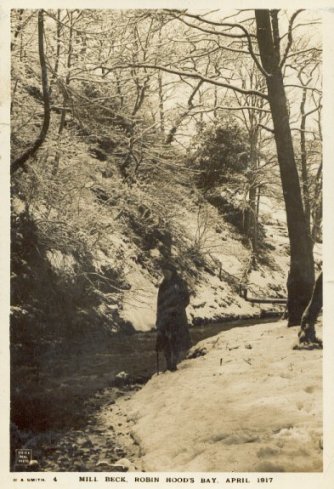

Mill (Ramsdale) Beck, Robin Hood's Bay, April 1917

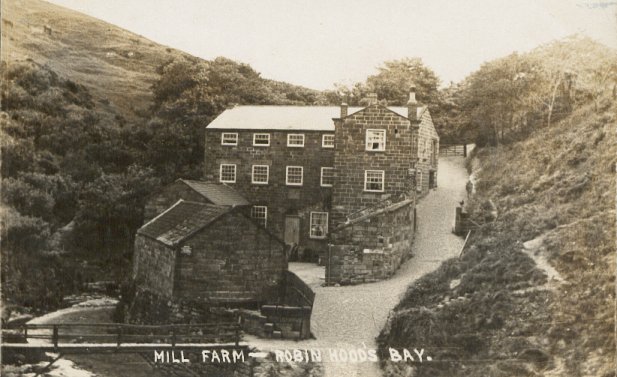

Mill Farm - Robin Hood's Bay

Mill (Ramsdale) Beck, Robin Hood's Bay

Satellite Image of Robin Hood's Bay, Ramsdale Hamlet, Ramsdale Beck and Ramsdale Megalithic Standing Stones

Ramsdale Megalithic Standing Stones, North Yorkshire

|

|

|

Access: Off the A171 to Whitby, just after B1416 junction a gate off to the right signposted Ramsdale leads through a cattle grid to a track across the moor. Half a kilometre on, just over the brow of the hill the track widens out where a small path crosses it. Turn right down the path and continue for 400 metres. Branch off across the moorland to the right another few hundred metres, and up to a raised area near a tumulus. Nearest town: Whitby |

The Moorland Road near Whitby

Lilla Howe Bronze Age Barrow, North Yorkshire

The round (bowl) barrow of Lilla Howe (SE 88929868) was constructed of earth and stone and measures about 20 metres in diameter and stands over a metre tall although it has been quite badly damaged over the years.

Bowl barrows are funerary monuments dating from the Late Neolithic period to the Late Bronze Age and most examples date from the period 2400 to 1500 BC. They were constructed as earthen or stone mounds, sometimes ditched which covered single or multiple burials. They often occupy prominent locations and hence have remained important elements in the landscape. Occasionally this led to their reuse at later periods. Their considerable variation in form and longevity as a monument type provide important information on the diversity of beliefs and social organisation amongst early prehistoric communities. A substantial proportion of surviving examples are considered worthy of protection.

The barrow has been partly excavated and reveals an assemblage of Anglo-Saxon and Viking grave goods. This shows that both the cross and the burials played an important part in the early medieval Christian perception of the landscape.

It was believed that Lilla Cross marked the grave of Lilla, chief minister to King Edwin of Deira. The legend relates how, in AD 626, Lilla saved the life of the king from assassination when he flung himself between the king and the dagger-bearing assassin. The king survived the attack but Lilla died and was buried in the existing tumulus and hence the name of the mound, Lilla Howe.

The story concerning Lilla, as recorded by Bede in AD 731 [2], is as follows:

"… there came to the kingdom an assassin whose name was Eomer, who had been sent by Cwichelm, King of the West Saxons, hoping to deprive King Edwin of his Kingdom and his life … He came on Easter Day to the King's hall which then stood by the River Derwent. He entered the hall on the pretence of delivering a message from his lord, and while the cunning rascal was expounding his pretended mission, he suddenly leapt up, drew the sword from beneath his cloak, and made a rush at the King. Lilla, a most devoted thegn, saw this, but not having a shield in his hand to protect the King from death, he quickly interposed his own body to receive the blow. His foe thrust the weapon with such force that he killed the thegn and wounded the King as well through his dead body."

[2] Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, eds B. Colgrave and R. A. B. Mynors (Oxford, 1969), Bk. 11, ch. 9, p. 165

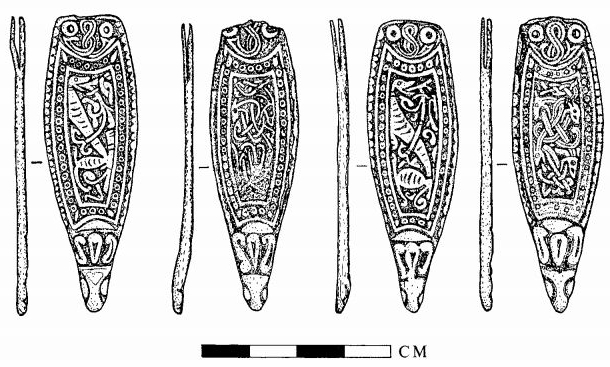

In 1981 Jeffrey Watkin and Faith Mann published a note, the stated purpose of which was "to draw attention to … four silver strap-ends said to be from the Bronze Age barrow known as Lilla Howe, North Yorkshire, (SE 88929868), and to consider the implications their date has for the frequent attribution of the barrow as the burial place of the Anglian noble Lilla, murdered in A.D. 626." Their "note", "Some Late Saxon Finds from Lilla Howe and their Context" published in Medieval Archaeology (1981) pages 153-157

- reviews the provenance of the small Viking hoard discovered at Lilla Howe

- confirms a Norse association with this area

- is summarised below

"Two gold discs and four silver strap-ends are thought to have been recovered from the Bronze Age barrow known as Lilla Howe [3] during its excavation in the late nineteenth century. Unfortunately little is known of the circumstances of the discovery of this important group of finds, but all the evidence points to them being found in Lilla Howe or its vicinity shortly before their first mention in print in 1871. However, from their first mention in print in 1871 the discs and strap-ends were said to be 'probably' from Lilla's grave, a likelihood converted to a certainty by Mr and Mrs F. Elgee who were able to write in 1933 of the "… only known Anglian interment in a Bronze Age barrow on the Eastern Moorlands [that] can be directly associated with an historical event … Lilla was undoubtedly buried in Lila Howe …". Largely thanks to this latter identification the notion that Lilla Howe contained a high status Anglian secondary burial has entered the archaeological and historical literature. However, an examination of these discs and strap-ends, now in the Mayer collection in the County Museum, Liverpool, shows that they post-date Lilla's burial by at least two centuries … It is clear though that the discs and strap-ends cannot be associated with any 7th-century burial, and in the absence of the mention of a body in the report of 1871 the notion of a 'Viking Age hoard' put forward by Wilson [4] seems quite plausible.

[3] Lilla Howe - Bronze Age round barrow, North Yorkshire (SE 88923 98687; 54.375873,-0.632766) at 292 metres (958 feet) above sea level.

[4] D. M. Wilson, Anglo-Saxon Ornamental Metalwork, 700-1100 (British Museum Publications, 1964), 19-20 n. 12; D. A. Hinton, 'Late Saxon treasure and bullion', in D. Hill (ed.), Ethelred the Unready: Papers from the Millenary Conference, British Archaeol. Reports, 59 (Oxford, 1978), 152

The Yorkshire Post, Saturday 9 February 1935 at page 8

This World of Ours by Northerner

Treasure Hunting in Tumuli

Someone has just been cordially agreeing with the opinion, which I gave the other day, that the worst foe of the genuine archaeologist is the amateur delver into tumuli. He tells me that Canon Atkinson, the Yorkshire antiquary, who himself explored many dozens of barrows in the Cleveland area, has left it on record that hardly any of the barrows he opened did not show signs of previous attempts to rifle them.

Most of these attempts would, however, date back to long before the days of amateur archaeology which is, in its universal form, of very modern growth. They were caused by that once popular, and not yet extinct, myth that the people of the past were in the habit of burying gold and silver. In some counties, written authority, under seal from the Sheriff of the county, was obtained by the treasure hunters to dig up this fictitious wealth. And many others worked secretly without any authority.

Of course they never found anything. Most of these tumuli contain nothing more valuable than the calcined bones of the dead in earthenware urns, a few flint implements, and sometimes a necklace of jet beads intended for the use of the departed in a future life. I believe the only objects of precious metal found in any Yorkshire tumulus are two shield-shaped gold ornaments, about four inches long, found in Lilla Howe, on the Goathland Moors. They are now in Liverpool Museum, and are said to be of Scandinavian origin.

|

|

Alternative place-name derivations for Lilla Howe

- Lilla could be based on the Swedish word lilla meaning 'little' giving "little cairn" (lilla haugr). Old Norse lítill meaning 'little' gives Lillemor, a Norwegian name derived from Norwegian lille, the weak declension of liten, 'little' from Old Norse lítill and mor 'mother' from Old Norse móðir.

- Lilla is also used as a diminutive of 'Elisabet' (compare 'Lilly'), a common Old Nordic name, giving 'Elisabet's cairn' (also lilla haugr).

- See also Lilla Vilunda runestones and Lilla Ullevi ("little shrine of Ullr").

- "… Lilhoue, there can be little doubt, contains the name Lilla …" per "On the Danish Element in the Population of Cleveland, Yorkshire" J. C. Atkinson published in The Journal of the Ethnological Society of London (1869-1870) Vol. 2, No. 3 (1870) at page 361

Click here to view Historic England List Entry No 1010076 (Lilla Howe) full scale map

|

|

| Silver strap-ends from Lilla Howe, North Yorkshire | Silver strap-end from the Cuerdale Hoard circa 900AD |

"Settlement and society in north-east Yorkshire A.D. 400 - 1200" (1987) Ann Elizabeth Reid at pages 32 and 33

The importance of Lilla Howe as a township boundary is of particular interest in that this Bronze Age barrow contains an intrusive burial of the Anglo-Saxon period. This was traditionally assumed to be the burial of Lilla, the thegn who died saving King Edwin from an assassin's dagger in 626 (HE II. 9, Watkin and Mann 1981), but recent research suggests a tenth century date and possible Viking origins (Morris. pers. comm). If this is so, it raises more questions than it answers. Could it be that the barrow retained its significance as a nodal point from the prehistoric era through to the tenth century, or did this significance only develop in the latter half of the Anglo Saxon period? Recent work by Fellows Jensen suggests that the tenth century was a period when, under the stress of the Viking invasions, a market in land developed for the first time and the old large estates were broken up (below 131-34). If this is indeed the case, it is possible that the significance of Lilla Howe as a boundary marker began only in this period. However, the barrow lies on the boundary between two of the great estates which seem to have survived the Viking Age substantially intact. Lilla Howe appears on the boundary of the modern townships of Fylingdales, Goathland, Lockton and Allerston and is one of the boundary markers of the liberty granted to Whitby Abbey by Alan de Percy (WCh I.No 27). Goathland does not appear in the earliest docurrents but both this township east of the Murk Esk and Fylingdales lie within the Whitby Liberty boundary. Lockton and one of the two tenurial units at Allerston belonged in 1086 to the royal multiple estate of Pickering, the other was a separate manor also held by the Crown and sub-tenanted by the native Cospatric (Faull 1985. 299b, 305a). Beyond Ebberston, immediately to the east of Allerston, almost all the Domesday settlements belonged in 1086 to the multiple estate of Falsgrave (see Map 9). As Ebberston township does not extend as far north as Lilla Howe, it seems likely that the barrow formed a boundary marker between the Whitby and Pickering estates and possibly also between these two and the Falsgrave estate. If this is so, can these estates be projected back earlier than the Conquest period?

Cuerdale Hoard, Preston, Lancashire

The Cuerdale Hoard contains more than 8,600 items, including silver coins, English and Carolingian jewellery, hacksilver, ingots and a single silver strap-end. It was discovered on 15th May 1840 on the southern bank of a bend of the River Ribble, in an area called Cuerdale in South Ribble near to the city of Preston, Lancashire, England.

The Cuerdale Hoard is one of the largest Viking silver hoards ever found, four times larger than its nearest rival in the British Isles, according to Richard Hall. In weight and number of pieces, it is second only to the Spillings Hoard found on Gotland, Sweden.

The design of the Cuerdale silver strap-end is similar to that of the fourth silver strap-end discovered at Lilla Howe and described by Jeffrey Watkin and Faith Mann (emphasis supplied):

"Silver strap-end (12.6.79.19; Pl. xiv, A, top right; Fig. 4). At the terminal is a formalized animal head in relief. The snout is plain, the eyes round, the ears formalized. At the split end there are four holes for two rivets. Between the rivet holes is a scroll design. The long sides each have a beaded edge. A single line of rings between two solid lines encloses the central panel. The rings become less well defined towards the terminal end of the object. In the central panel are four animal heads, with gaping jaws, two on each side of the panel. The bodies of these creatures are interwoven and help to form the ribbon-like interlace covering the remainder of the panel. The back of the object is plain. Length 62.5 mm.

All six items have been published before, but not together. The two gold discs were illustrated and discussed in 1961 by Professor V. I. Evison, who suggested that they may be English, possibly Northumbrian, products, apparently of the 9th century. However their closest parallels seem to be Scandinavian and both Dr D. M. Wilson and Mr D. A. Hinton feel they could well be imports, the latter favouring a date as late as the 10th century.

The strap-ends have also been illustrated before, in an article by E. T. Leeds in 1911, although he was not aware of their provenance or their association with the discs. Strap-ends with stylized animal-head terminals are well known from middle and late Saxon contexts, nearby examples from Whitby, N. Yorks. being attributed to the early 9th century. However the details of the zoomorphic ornament on the central panels are more difficult to parallel. Only the first pair of strap-ends, with a single animal in the central panel, shows any close similarity to any other yet published. The animal ornament here is very like that on a strap-end from the Talnotrie hoard, deposited c. 875.

… It is clear though that the … strap-ends cannot be associated with any 7th-century burial, and in the absence of the mention of a body in the report of 1871 the notion of a 'Viking Age hoard' put forward by Wilson seems quite plausible."

per Jeffrey Watkin and Faith Mann at pages 155 and 156

The authors conclude that:

From the archaeological evidence reviewed above it is clear that there is no justification for the secondary Anglo-Saxon barrow burial plotted by the Ordnance Survey or its identification with a specific personage … The theory that this was his mound seems to have arisen from the fortuitous juxtaposition of the appropriate barrow name and an appropriate river name, combined with the location of Saxon period finds of whose late date not all writers are aware. The only possibility by which these finds could be related to a 7th-century burial is if the missing material is some two centuries earlier than that examined here, and this seems unlikely. Instead, the presence of an important Viking Age 'hoard' from this site should perhaps be more widely appreciated and the material gain the attention it deserves.

The Cuerdale Hoard

8,600 9th century Viking silver items buried between 905 and 910.

The hoard is the largest collection of Viking silver ever discovered outside Russia.

The Watchman, Wednesday 26 August 1840 at page 275

Inquisition on the coins found at Cuerdale

Last Saturday, an interesting inquiry took place at the Bull Inn, Preston, before John Hargreaves, Esq., coroner for the Blackburn hundred, and a respectable jury of sixteen persons, "touching the finding and discovering of certain silver coins and other things, alleged to have been discovered in the township of Cuerdale." Thos. Starkie, Esq., Q.C, officiated as assessor for Mr. Hargreaves. The inquiry was conducted under the provisions of a statute of Henry the First, which directs, that when any treasure is found, the coroner shall summon a jury to inquire into the circumstances of the find, and to ascertain whether the treasure does or does not belong to the crown.

A large degree of interest was excited on the occasion, inasmuch as it was known that the coins, &c., (which were found on the 15th of last May,) were of considerable value as well as of great rarity, and that two parties had put in claims to their ownership, viz., the Queen, in right of her Duchy of Lancaster, and Wm. Assheton, Esq., of Downham Hall, near Clitheroe, as lord of the manor of Cuerdale, and owner of the land on which the discovery was made. The claims of the respective parties were supported before the coroner's assessor by gentlemen of the long robe, Thos. Flower Ellis, Attorney-General of the Duchy, and John Teasdale, Esq., Solicitor-General of the Duchy, appearing on behalf of her Majesty, and John Addison, Esq., on behalf of Mr. Assheton.

The articles found are all of silver: they may be divided into four classes, viz., coins, large bars or ingots, small bars or ingots, and ornaments. Of the coins there are an immense number; not less, it is calculated, than 6,800. Their weight is just 304 oz. Troy, and they consist chiefly of Anglo-Saxon coins, with a smaller number of French, and a few Cufic or Oriental. Some of the Anglo-Saxon are of the reign of St. Edmund, from 855 to 871, but coined after his death, as is evident from the word "sanctus" upon them; some are of the reign of Alfred from 871 to 899; the principal part of them are of the reign of Edward the Elder, from 900 to 925; and one only is of the reign of Athelstan, the natural son and successor of Edward the Elder. The French coins are chiefly of the reign of Charles the Bald, Lewis the Stammerer, and Lewis the Second; besides which, there are some whose dates are not known by any collector. The latest French were coined in 879. Of the Oriental coins, although they bear no dates, it is the opinion of persons learned in numismatics, that they are contemporary with those already mentioned. There are sixteen large bars or ingots, averaging 6¼ oz., and weighing in the aggregate 132 oz. Each of these has a cross upon it, and they are said to be marks, being of the value of 160 of the smaller coins, and of course used in the payment of large sums as we now use paper. Of the smaller ingots there is a large number; they weigh altogether 725½ oz., and are supposed to be parts of a mark, some of these being so small as to represent only three of the coins; these are said to be the Anglo-Saxon coin called "thrimsa". The ornaments consist of rings, bracelets, chains, &c., which appear to have been crushed up together, as though crammed into a box in the hurry of hiding; they weigh 103½ oz. The total weight of the silver is 1,265 oz., which, at the rate of 4s. 6d. per ounce, is worth £284 12s. 6d. though of course its value in the "antiquarian market" is considerably more.

The reader is already aware that this large and interesting treasure was discovered close by Cuerdale Hall [SD 57707 29438] on the 15th of last May by some workmen who were making alterations to prevent further encroachments on the banks of the Ribble. It was about a yard from the surface in the then existing state of the ground, and perhaps 50 yards from the present bank of the river, and seems to have been enclosed either in a leaden box, or a wooden box with a leaden lining.

It is conjectured it was deposited in the place wherein it was found in the early part of the reign of Athelstan, and the ground upon which this conjecture is founded is, that there are numbers of coins of the reigns of Athelstan's immediate predecessors, while there is only one of his own reign, although Athelstan's coins are exceedingly common, and to be found in tbe possession of every collector.

It is also further conjectured that, as a great battle was fought near Bansbury, in Northumbria, which was then subject to the Danes, in the beginning of Athelstan's reign, the treasure was hidden by some person going to join Anlaf, who was defeated by Athelstan, and being killed, came not back to claim it.

Editor's note: the "great battle … fought near Bansbury, in Northumbria" is most likely a reference to the Battle of Brunanburh, which was fought in 937 between Æthelstan, King of England from 927 to 939, and an alliance of:

- Olaf Guthfrithson (ON Óláfr Guðrøðsson; OE Ánláf; OIr Amlaíb mac Gofraid) (i.e. Anlaf), King of Dublin;

- Constantine II, King of Scotland, and

- Owain, King of Strathclyde

The battle is often cited as the point of origin for English nationalism and one of the most significant battles in the long history not just of England, but of the whole of the British Isles. Several thousand Norsemen fell, which casualties included five kings and seven earls from Olaf's (Anlaf's) army.

As to the inquiry into the ownership of these interesting relics of former ages, after a long investigation, the jury retired to consider their verdict, and upon returning into court, having been absent about ten minutes, the foreman said,

"we find the articles are the property of her Majesty in the right of her Duchy of Lancaster, as treasure-trove."

Blackburn Standard.

The Watchman, Wednesday 1 December 1841 at page 382

Science, Literature, Art, &c

Numismatics

At a meeting of the Numismatic Society on Thursday evening, the secretary announced, among other presents, a valuable donation from her Majesty the Queen (through the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster) of specimens of the silver pennies and halfpennies found last year at Cuerdale, near Preston.

Many of these coins are of the first rarity, and a great number unpublished. They are of Alfred the Great, of Archbishops Plegmond and Cœlnoth, and the mint of St. Edmund's Bury, of Charlemagne, Louis I and II, Carloman, Charles le Chauve, Eudes, &c., and a great number of other foreign pieces, evidently of the same period, but of princes and towns hitherto unknown on coins. Edward Hawkins, Esq., is engaged in a careful investigation of these interesting historical records.

The Watchman, Wednesday 15 February 1843 at page 54

Science, Literature, Art, &c

Miscellaneous

Forgers of Ancient Coins

It was announced at a late meeting of the Numismatic Society, that imitations had been fabricated of the Anglo-Saxon coins discovered about two years since at Cuerdale, in Lancashire, and that at the present moment persons are travelling to various towns, and disposing of them to coin collectors, and to the curators of museums &c. As these imitations are extremely well done, it is to be feared that many will be sold before suspicion is excited. Among the coins recently forged, are the rare pennies of Alfred, Harold, Canute, the early Henries, and Stephen, and coins of Edward the Sixth, Philip and Mary, and the scarce "ryall" of the last-mentioned sovereign.

"An account of the Danes and Norwegians in England, Scotland, and Ireland" (1852) Jens Jakob Asmussen Worsaae, at pages 48 and 49

Some few years ago (1840), a highly remarkable and very ancient treasure of silver was discovered near Cuerdale in Lancashire, within the boundaries of the ancient Northumberland. It consisted of bars, armlets, a great number of pieces of broken rings and other ornaments, as well as about seven thousand coins, all of which were inclosed in a leaden chest.

To judge from the coins, which, with a few exceptions, were minted between the years 815 and 930, the treasure must have been buried in the first half of the tenth century, or almost a hundred years before the time of Canute the Great.

Amongst the coins, beside a single Byzantine piece, were found several Arabic or Kufic, some of north Italy, about a thousand French, and two thousand eight hundred Anglo Saxon pieces, of which only eight hundred were of Alfred the Great.

But the chief mass, namely, three thousand pieces, consisted of peculiar coins, with the inscriptions "Siefredus Rex", "Sievert Rex", "Cnut Rex", "Alfden Rex" and "Sitric Comes" (jarl); and which, therefore, merely from their preponderating number, may be supposed to have been the most common coins at that time, and in that part of north England where the treasure had been concealed.

Cnut's coins were the most numerous, as they amounted to about two thousand pieces of different dies; which proves a considerable and long-continued coining.

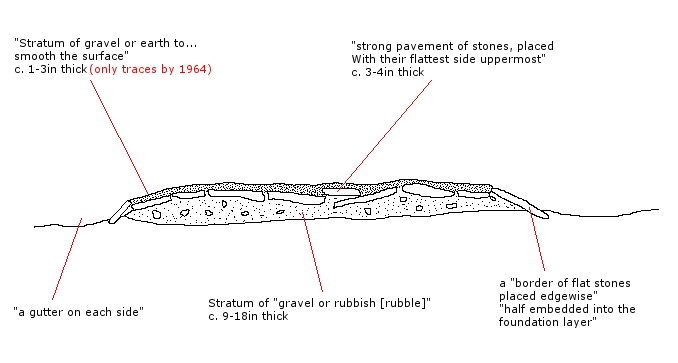

Wade's Causeway, North Yorkshire

Another possible Norse association with this area is Wade's Causeway ("Wheeldale Linear Monument"), a sinuous, linear monument up to 6,000 years old in the North York Moors national park in North Yorkshire, England. The name may refer to either:

- scheduled ancient monument number 1004876 - a length of stone course just over 1 mile (1.6 km) long on Wheeldale Moor, or

- a postulated extension of this structure, incorporating ancient monuments numbers 1004108 (two sections of Roman road on Pickering Moor) and 1004104 (two sections of Roman road on Flamborough Rigg) extending to the north and south for up to 25 miles (40 km).

The visible course on Wheeldale Moor consists of an embankment of soil, peat, gravel and loose pebbles 0.7 metres (2.3 ft) in height and 4 to 7 metres (13 to 23 ft) in width. The gently cambered embankment is capped with unmortared and loosely abutted flagstones. Its original form is uncertain since it has been subjected to weathering and human damage.

Wade's Causeway (section)

Wade's Causeway (1984)

The structure has been the subject of folklore in the surrounding area for several hundred years and possibly more than a millennium. Its construction was commonly attributed to a giant known as Wade, a figure from Germanic or Norse mythology. It is not known for certain who the causeway is named after, but the figure was at the latest pre-Renaissance, and the majority of sources agree that it has its origins in the medieval period or earlier.

The Wades in early English works likely relate to one or more earlier legendary figures known as Wade, or variations thereof, in Northern European folklore and legend. Various authors suggest links to, among others, the giant Vaði, (also known as Witege, Vathe, Vidia, Widga, Vidga, Wadi or Vade) mentioned in the Norse Saga of Bern in the þiðrekssaga.

Skivick

It is thought that Skivick or Skivik, the local name for the section of structure visible on Wheeldale Moor, could derive from two morphemes from Old Norse. The first syllable could derive from skeið, which could mean either a track or farm road through a field, or from a word used to describe a course or boundary. The second syllable could derive from vík, meaning a bay or a nook between hills. Scandinavian or Norse place-names are common in Yorkshire and Norse peoples settled in the Yorkshire area from 870 AD onwards following raiding over the previous seventy years. Sawyer states that early Norse colonists had a profound effect on place-names in the areas in which they settled. Sedgefield states that the skeið derivation specifically in place-names within northern England points to Scandinavian settlement of the area, but that due to the inheritance of language across generations, a place-name containing skeið may in any individual case have been applied any time between the ninth and fifteenth centuries. Historian Mary Atkin states that skeið place-names appear near Roman sites frequently enough to suggest an associative link.

A wide variety of interpretations for the structure have led, in the absence of any hard evidence, to a broad range of proposed dates for its construction, from 4,500 BC to around 1485 AD. In archaeological excavations, no coins or other artefacts have been found on or around the structure to aid its dating, and no evidence has been gathered as of 2013 through radiometric surveys. This has led to great difficulty in establishing even an approximate date for the causeway's construction. Attempts to date the structure have therefore relied on less precise means including etymology, the structure's probable relationship in the landscape to other structures of more precisely established date and function, and the comparison of the causeway's structure and fabrication to structures such as Roman roads.

To account for the uncertainty regarding the structure's original function, the term "Wheeldale Linear Monument" was introduced in 2010 to refer to the structure. English Heritage in 2013 stated that the balance of opinion had swung to favour a prehistoric, rather than Roman, origin for the structure. As of 2013, the uncertainty regarding the monument's purpose and origin is reflected by the information board at the end of the Wheeldale section of structure, where it meets the modern road. The original sign, pictured in 1991 states that the structure is a Roman road, whereas new signage installed in 1998 admits that the origin and purpose of the structure are unknown.

As of 2013, the site is managed by the North York Moors National Park Authority, in cooperation with English Heritage, through a Local Management Agreement. English Heritage do not man the site and permit free access at any reasonable time. The site receives up to a thousand visitors per month.

The Yorkshire Post, Saturday 30 September 1933 at page 8

Romance of a Roman Road

"Wade's Causeway" on Wheeldale Moor by Rutherford Crockett

One can do the Roman Road of Wheeldale in half-an-hour, climbing the well-marked track from Wheeldale lodge across the beck. That is, one can pant up the steep ascent, survey the excavated portion of the Road, read and ponder the admonitions of His Majesty's Office of Works which adorn its course, and be back in Goathland village in time for tea, or in York city, with a car, in time for dinner.

But to get on terms with such a Road as this, one should live, if not on it, at least so nearly on it that it is accessible at any hour of day or night. One should explore the surrounding moorland on foot in all directions, from Stape hamlet on the one hand to Egton Bridge on the other. One should spend the fire-lit evenings with a copy of that intimately delightful book, Canon Atkinson's "Forty Years in a Moorland Parish"; with, perhaps Frank Elgee's study of the Yorkshire moorlands as a supplementary record. At the end of a September fortnight of this regime, if the Roman Road has not acquired a personality of its own, and does not draw the footsteps with a certain magnetism easier to feel than to describe, then there is no more to be said, and the traveller had better try Paris or Switzerland for his next autumn holiday.

Lying in the heather on the high moorland, the traveller may capture two prizes almost unknown to the modern world: Complete solitude and complete silence. He shares the stony track, laid by Roman hands so long ago, with the black-faced moorland sheep that browse about its edge, and serenely progress along its harsh uneven surface with an agility and poise which few pedestrians achieve. Now and then an earnest, perspiring "hiker" bound for Levisham or Lockton, passes by; but for those solemn visitations by learned members of archæological societies, in full panoply of umbrellas, reference books and substantial sandwiches, the season is already too far advanced. Such have returned home in modest triumph, and the lectures and slides destined for winter study circles are already well under way.

Sounds there are few. The grouse call persistently enough, "Come back! Come back! Come back", and as persistently the shades of those Roman road makers ignore the summons. At sundown, from the encircling moor-slopes, come the cries of sheep being rounded up by dogs, the shrill rap-rapping of the collies punctuating the plaintive notes of the flock. Occasionally, in the still hours of early afternoon, a roving 'plane crosses the road, high up in the blue distance. Last week a squadron of nine, flying low, floated like legendary silver swans over the burial "howes" on the moor-slopes, startling the birds in their flight, and then drifting off eastward, leaving the road to its solitude and the graves to their forsaken dignity.

Those memorials of the distant dead, so frequent hereabouts, give to these dales a strange tinge of melancholy charm. "Standing stones", too, abound, jutting up grey and stark against their heathy background; so that one echoes Stevenson almost unconsciously:

Grey, recumbent tombs of the dead in desert places,

Standing stones on the vacant, wine-red moor;

Hills of sheep, and the howes of the silent vanished races,

And winds austere and pure.

If, by the way, those misguided compilers of anthologies who for so many years wrote homes for howes in that third line, had glanced at these Yorkshire burial-mounds or "howes", we should have been spared much controversy, and the shade of R. L. S. a gratuitous insult to his intelligence.

The Commissioners of His Majestys' Works announce themselves to-day with pardonable pride as "the Guardians of the Road". But the pioneer hands which led to the resurrection of the long-buried road were those of a guardian of the moor, by name James Patterson, by calling head gamekeeper under the Duchy of Lancaster, who is at the moment my host. This hardy Aberdeenshire Scot, of inquiring disposition and patient habit, chanced to hear an aged tenant-farmer in the district speak of "Aud Wade's Wife's Cassor" or Causeway, the course of which lay over Wheeldale Moor. Not content with local legends of "Aud Wade" (who provided his wife, so the tale runs, with the causeway so that she could reach the moors dry-shod to milk her cows), James Patterson went about his task of burning off "swizzens" or swiddens (large burnt patches of heather), with a sharp eye for traces of Wade's Road beneath. The peak of a kerbstone jutting above the peat's surface rewarded him; some stout spadework soon revealed paving, and the Roman Road was resurrected plain to view in the sunlight of the twentieth century. One or two learned friends were conducted to the scene, and these in their turn, approached His Majesty's Office of Works, with the happy results which delight antiquarians and thrill even the casual tourist of to-day. But the memory which still causes the first "Guardian of the Road" to chuckle over the fireside as he tells the story, is of a man from Stape who chanced upon the hardy Scot at his moorland digging; could not account in any way for such a "daft-like" occupation, and asked bluntly, "You'll be paid for this job?" On being told no, he hazarded the pitying comment, "Ah, well, you're out of work, I suppose."

Standing on the road overlooking Wheeldale, the most cursory traveller finds himself willy nilly, leaping from the Ice Age to the Bronze in a series of mental gymnastics. That immense lobe of ice which some 10,000 to 20,000 years ago, filled up this dale, has left very definite traces in the contours of Wheeldale as they are today. And all around, from Two Howes Rigg above Goathland, to Three Howes Rigg on Egton High Moor, are these burial-places of the Bronze Age, with the stony, cream-coloured roads or tracks skirting round them - roads which, as some say, may well be even older than the graves to which they served to carry the dead on their last moor-journey.

As one stands here, local lore can even forge a "well-found" link between Agricola of this Road and Napoleon, for there is Stephen Wilson's cave, a huge overhanging boulder across the moor yonder. Here, in the Waterloo campaign, the activities of the Press-gang drove the said Stephen to hide for safety. Cramped quarters he must have had, for the entrance is narrow and awkward enough, but there is a friendly tree firmly wedged among the stones encircling his refuge, from whose branches he may well have spied out the land for his captors' approach by clay, and watched eagerly at dusk for the stealthy coming of his wife across the moor with bite and sup for her man in his distress.

But the "roke" (that wet fog with a sea-tang in it, drifting over from Whitby way, and first-cousin, surely, to the "easterly haar" of the Firth of Forth) is creeping up over the moor towards the Road, shrouding every outline in a grey mist, dim as the shadowy past, in which the mind gropes and wanders. Time to make for home, down the steep slope to the stepping-stones, where across the singing beck, a lamp burns in the welcoming window. Time to leave the Road for the night to its unseen guardians shades of the men who made it, whose feet make no sound now on the stones in the dusk. Time to hasten by the tall grey trees, mist-haunted, which "sough" so gently beside the beck; and time, perhaps, to recall Housman's unforgotten. words, as one hears that poignant music and looks back towards the Roman highway:

"The tree of man was never quiet;

Then, 'twas the Roman; now 'tis I."

The Yorkshire Post, Saturday 23 November 1935 at page 10

Correspondence

Roman Yorkshire: Further Exploration of Wade's Causeway

Sir, May I call the attention of those interested in Roman Yorkshire to the work of Mr. James Patterson, of Wheeldale Lodge, Goathland.

Mr. Patterson is Warden of that fine length of Roman road on Wheeldale Moor, known as Wade's Causeway, which has been excavated by the Board of Works, and which is, or ought to be, known to all lovers of the Eastern Moorlands. Despite his great age, for he has passed man's allotted span, Mr. Patterson has of recent years investigated the further course of this road, more especially in Eskdale between Grosmont and Aislaby. He has traced it in a plantation west of Aislaby village, alongside the present road from Aislaby to Egton. He has uncovered part of the pavement, which presents features characteristic of Wade's Causeway on Wheeldale Moor - it has similar kerbstones, the same width (16-18 feet), a similar camber, and a similar elevation of from 2-3 feet above the ground level.

Mr. Patterson has made a solid contribution to our knowledge of a Roman road the course of which in the Aislaby region was practically unknown. Inspired by a love of the road itself, he has attacked the problem in the true spirit of field archæology, feeling his way with the spade. He has erected a memorial stone inscribed "The Pathway of the Romans" on the site.

There is no more fascinating task for the lover of the mysterious English countryside than that of tracking Roman roads the courses of which are not sufficiently well known, to be mapped. But it must be carried out with common sense and a rigorous testing of theories with the spade. Mr Patterson has set an admirable example of this kind of work, and his results will go far towards solving what has hitherto been an archæological mystery - the age, objective, and purpose of Wade's Causeway.

Yours,etc., Frank Elgee, Dorman Memorial Museum, Middlesbrough.

The Yorkshire Post, Monday 4 January 1937 at page 13

Hunting Runs and Appointments

Beagles: Two Hours' Hunt

Ampleforth College Pack's Good Feat

…

Then the pack settled down to some excellent hunting through the long and the "swiddened" heather, making right-handed across Wheeldale Moor towards Wheeldale Beck, and then left-handed to Wheeldale Ghyll, where they checked on the valley side. Welch then made a left-handed cast and hounds put up their hare, which ran down the slope, and the pack was once more at fault. As he was making another left-handed cast a single hound hit off the line and brought the pack working up the slope, where she was finally viewed and pulled, down in the heather.

This was a hunt of 2 hours, and included a 3½ mile point from Head House Farm. It is among the finest of the pack's moor hunts since 1922, and a fitting conclusion for the year 1936, in which hounds have shown some excellent sport.

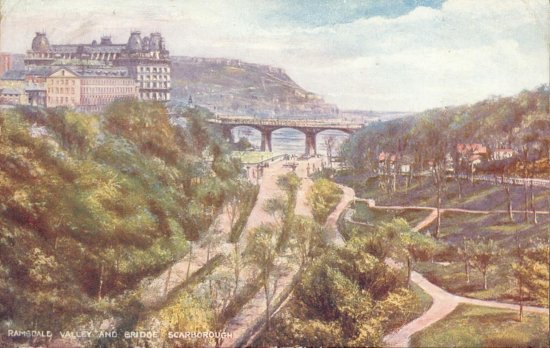

Ramsdale Valley, Scarborough, North Yorkshire

In Scarborough there is a park on each side of the Ramsdale valley, which is crossed by the Cliff Bridge, built in 1827, and the Ramsdale Valley Bridge, opened in 1865.

Ramsdale Valley (once the scene of corn mills) became the People’s Park in 1860. The main road through the valley (formerly Mill Lane) was completed in 1861. People's Park was named Valley Gardens in 1912.

Bulmer's History and Directory of North Yorkshire (1890): The People's Park. - This name has been given to Ramsdale Valley, commencing near the Aquarium and extending towards Falsgrave. It is thickly wooded, and tastefully laid out, with numerous walks and seats. A path branching to the right, under a splendid avenue of lofty trees, leads to the railway station. Further up is the fish pond, while many rare swans, geese, and other fowls of various plumage add picturesqueness to the scene.

Click on image to view other Edwardian postcards of Ramsdale Valley, Scarborough and Ramsdale Mill, Robin Hood's Bay

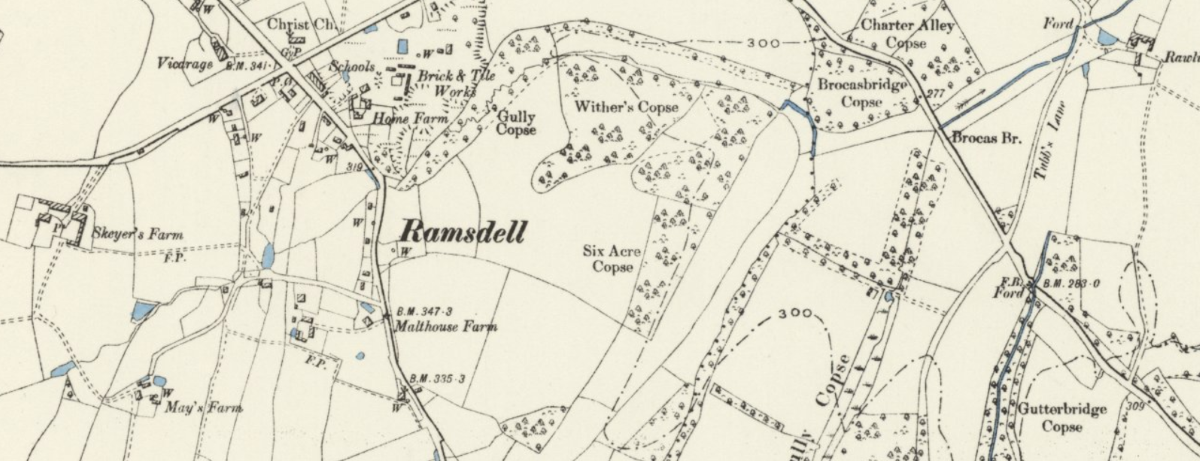

Ramsdale & Ramsdell Chapelries, Hampshire

The surname may also indicate an individual from one of two Hampshire parishes - Ramsdell and Ramsdale:

Ramsdell is part of the parish of Wootton St Lawrence, Chuteley Hundred, Hampshire - Wudutune, Wudetone (x cent); Odetune (xi cent); Wutton, Wotton (xiii cent); Laurence Wotton (xvi cent).

The parish of Wootton St Lawrence covers a long strip of land stretching from Tadley and Baughurst in the north to Deane and Kempshott in the south. Tadley is a parish in the north of Hampshire on the borders of Berkshire situated about 4 miles south from Aldermaston station on the Newbury and Devizes branch of the Great Western Railway and 6½ miles north west from Basingstoke.

The place-name Rammesdelle (Kitchin, op. cit. 58) (xiii cent) appears in local records. Ramsdell, formerly a tithing in the north of this parish, was formed into a separate ecclesiastical district in 1868. The church, Christ Church, was built in 1867 of flint with stone dressings in 13th century style, and consists of chancel, nave and tower with spire. The registers date from 1868. The living of Ramsdell is a vicarage, net yearly value £275, in the gift of the Bishop of Winchester. There is also a Congregational chapel at Ramsdell.

Ramsdale: The consolidated chapelry of Ramsdale, in the parish of Tadley, Overton Hundred, Hampshire - Taddele, Tadeleye (xiii cent); Tadelegh, Taddelegh (xiv cent); Tadele (xv cent).

Ramsdale Church, Hampshire

The Rose Inn, Ramsdale

Tadley is a parish in the north of Hampshire on the borders of Berkshire situated about 4 miles south from Aldermaston station on the Newbury and Devizes branch of the Great Western Railway and 6½ miles north west from Basingstoke. Part of the parish was assigned to the consolidated chapelry of Ramsdale on 15 January 1869 (London Gazette 15 January, 1869 at page 219).

The following description is taken from History, Gazeteer and Directory of the County of Hampshire by William White (1878, Simpkin Marshall & Co):

"RAMSDALE or Ramsdell is a pleasant village, 4 miles N. of Wootton Church, in Wootton St. Lawrence parish, but its ecclesiastical district, formed in 1869, comprises also parts of the mother parishes of Monk (or West) Sherborne and Tadley, and had 555 inhabitants in 1871. The church (Christchurch), a neat Early English structure of flint, with red brick facings and Bath stone dressings, consists of nave, chancel, and south porch, and was erected in 1867, at the cost of £1,100, raised by subscription, chiefly through the exertions of the Rev. W. B. Wither, the late vicar of Wootton St. Lawrence. The east window, a triplet, is filled with beautiful stained glass, representing the Resurrection, in memory of the mother and sister of the vicar; the two single lights in the south wall of the chancel are similarly enriched, as memorials of his father and son. The living is a vicarage, valued at £300 a year, in the patronage of the Bishop of Winchester, and incumbency of the Rev. Joseph Fuller M.A., who has a vicarage house, erected in 1869, at a cost of £2,000, mainly contributed by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. Attached to the residence are pleasant grounds; with a glebe of 30 acres, part of the above-mentioned endowment. The United School Board district of Wootton and Tadley has a school here. In the village are very large brick and lime works, and near it a chalk-pit, in which fossils have been found. The heath is let out in allotments to poor people."

The following description is taken from Kelly's Directory of Hampshire (1898):

RAMSDALE (or Ramsdell) is an ecclesiastical parish, formed in 1868 from the parishes of Monk Sherborne, Tadley and Wootton St. Lawrence; it is on the road from Basingstoke to Newbury, 5 miles north-west from Basingstoke station on the London and South Western main line to Southampton, in the Northern division of the county, hundred, petty sessional division, union and county court district of Basingstoke, rural deanery of Silchester and archdeaconry and diocese of Winchester. Christ Church, built in 1867, at a cost of about £1,400, is an edifice of flint with stone dressings, in the Early English style, consisting of chancel, nave and a tower with spire containing one bell: nearly all the windows are stained: there are 145 sittings. The register dates from the year 1868. The living is a vicarage, net yearly value £275, with residence, in the gift of the Bishop of Winchester, and held since 1896 by the Rev. Charles Rowlandson Durham M.A. of Merton College, Oxford. Here is a Congregational chapel. The principal landowner is Sir Edward Percy Bates bart. of Beechenhurst, Allerton, Liverpool. The soil is loam; subsoil, clay. The chief crops are wheat, oats and barley. The population in 1891 was 449.

Charter Alley, 1 mile north-east, is in the civil parish of Monk Sherborne, but ecclesiastically in Ramsdale.

Board School (mixed), built in 1877, and under the control of the Wootton & Tadley School Board: it will hold 120 children; average attendance, 104.